‘The Free State of Jones’, and Its Leader Newt Knight in His Own Words

Most of us have probably seen the movie, ‘The Free State of Jones,’ starring Matthew McConaughey and directed by Gary Ross. (If not, you can still rent it cheaply from YouTube or Amazon Prime). It’s based on a true story previously buried in our lost history. It tells the tale of a pro-union and anti-slavery group of interconnected families–white, Black, and mixed–in one Mississippi county during the Civil War and after. The Jones County residents banded together in refusing to secede from the Union. Led by Newt Knight, these men had been conscripted into the Confederate Army, deserted, or dodged the draft entirely. A few were escaped slaves.

When the CSA tried to enter Jones County to capture them, they were defeated at every turn. Jones County wanted to stick with the Union and have their fighting men mustered into the Union Army, but they could never make contact to be ‘sworn in.’ Hence the ‘Free State’ of Jones County. After the war, when the ex-Confederates tried to destroy the Reconstruction governments, Jones County fought with the Blacks, holding out for decades.

These two paragraphs give us the story’s heart, but there’s much more to it. Luckily, an enterprising reporter from the New Orleans Times-Picayune, James Karst, back in 1921, rose to the task. He managed to track down Newt Knight, then 91 years old, and got him to tell his story on his own terms. We’ll include it here, adding a few italicized or bracketed facts now and then for context.

This interview with Newton Knight of Mississippi was originally published in the March 20, 1921, edition. It was believed at the time to have been the only time Knight spoke to the press about the Free State of Jones.

Karst put a summary statement up front: “We’ll all die guerrillas, I reckon,” Knight mourned. “Never could break through the rebels to jine the Union army. They neveh did break through to jine us. Th’ Johnny Rebs busted up the party they sent to swear us in. Always was unofficial. Well, I reckon it don’t make much difference now, anyhow.” But he went on to unfold the larger story.

“Past the white skeleton of a lightning-blasted pine we made our way by the winding forest path. And as we headed down the steep hill, the bushes at the foot parted. A tall form emerges.”Lord, that’s luck,” said the guide. “It’s Uncle Newt himself.”

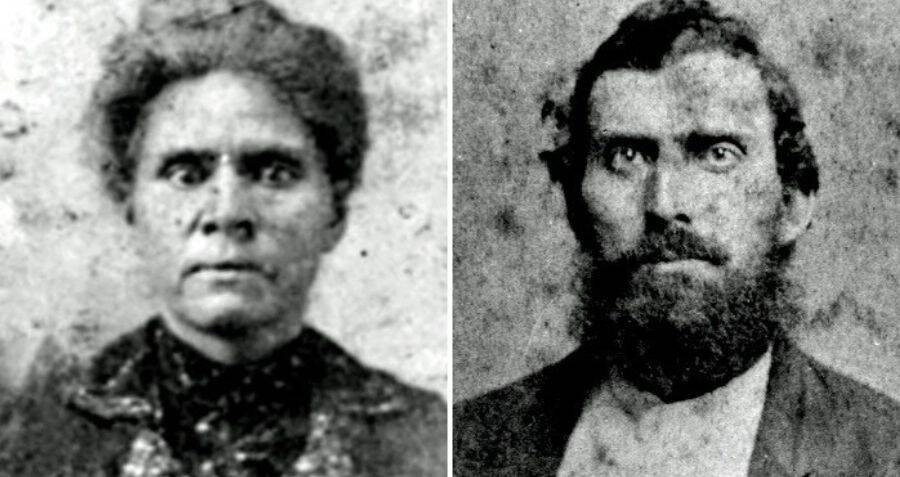

(Knight was 6-foot-4 with black curly hair and a full beard—“big heavyset man, quick as a cat,” as one of his friends described him. He was a nightmarish opponent in a backwoods wrestling match, and one of the great unsung guerrilla fighters in American history. So many men tried so hard to kill him that perhaps his most remarkable achievement was to reach old age.)

Draw your own picture of a 91-year-old veteran climbing a steep hill by a narrow path through thick-woven underbrush at the end of a three-mile tramp. It won’t be the sight that greeted my eyes. The shoulders of the tall, gaunt form that mounted the hill were a trifle stooped. At that, not much more than many a city desk-stoop in men half his age. From heavy boots up a dark suit of homespun my eyes traveled, and stopped just below the great hat of light-colored felt — “white hats” they call them on the Texas range. For the face beneath that wide hat-brim would arrest attention anywhere.

A might beak of a nose jutted out like a promontory. The jaw was seen through a sparse white beard. The white hair, uncut for years, hung about the shoulders. But the eyes held you longest. They were that cold, clear grey-blue eye of the killer now vanishing from the West. They looked clear through you. And by some peculiarity of control, hawk-like, the lower lids never moved.

My guide presented me with the customary formula.

“Glad to see you, sir,” said Uncle Newt, shaking hands. His grip still had power. His hands were oddly full and muscular; not shrunken with his great age. “Come on up to the house. I’m feelin’ right peart this morning, but I reckon a little fire would feel good, don’t you?”

Into the plain match-boarded living room of the house we went, where oak logs were roaring in the white-washed fireplace.

“Draw up a cheer and make yourself comfortable,” said Uncle Newt, cordially. “Now sir,” spoke up our 91-year-old host, “what is it you want me to tell you?”

“Uncle Newt,” said I, “there’s a lot of stories going ’round about you and your company in the Civil War. Nobody seems to have your own story of it, yet. And folks say you were pretty busy out here in Jones and Jasper counties for awhile. Suppose you tell it to us just the way you remember it.”

“Well, I remember a right smart of it,” conceded Uncle Newt. “Memory still good as your eyes?” I asked. He was without glasses.

“Better,” said he, promptly. “My memory’s all right. ‘Bout my eyes: I’ve worn out three-four pair spectacles. Don’t think much of ’em. Quit ’em. I can see enough to shoot a bird on the wing or a rabbit on the run yet. That’s good enough for me.”

“He can shoot ’em that way,” spoke up his granddaughter. “Keeps us supplied with birds and rabbits all the time. His memory — well, you ought to hear the old songs he sings to us.”

Uncle Newt smiled at that. And then, spurred by occasional questions, he launched into his story.

“They used to call Jones County, Mississippi, the Free State of Jones,” said he. “That started a lot of stories about the county. There’s one story that after Jones County seceded from the Union she seceded from the Confederacy and started up a Free State of Jones. That ain’t so. Fact is, Jones County never seceded from the Union into the Confederacy. Her delegate seceded. When the Southern states was all taking a vote on whether to secede, we took the vote in Jones County, too. There was only about 400 folks in Jones County then. All but about seven of them voted to stay in the Union. But the Jones County delegate went up to the state convention at Jackson, and he voted to secede with the rest of the county delegates. He didn’t come back to Jones County for awhile. It would ‘a’ been kinder onhealthy for him, I reckon.

“Well, we’d voted agin secession, but the state voted to secede. Then next thing we know they were conscripting us. The rebels passed a law conscripting everybody between 18 and 35. They just come around with a squad of soldiers ‘n’ took you.

“I didn’t want to fight. I told ’em I’d help nurse sick soldiers if they wanted. They put me in the Seventh Mississippi Battalion as hospital orderly. I went around giving the sick soldiers blue mass and calomel and castor oil and quinine. That was about all the medicine we had then. It got shorter later.

(Knight and many other Piney Woods men deserted from the Seventh Battalion of Mississippi Infantry. It wasn’t just the starvation rations, arrogant harebrained leadership and appalling carnage. They were disgusted and angry about the recently passed “Twenty Negro Law,” which exempted one white male for every 20 slaves owned on a plantation from serving in the Confederate Army. Knight said he’d enlisted with a group of local men to avoid being conscripted and then split up into different companies.)

“Then the rebels passed the Twenty Negro Law, up there at Richmond, Virginia, the capital. That law said that any white man owning 20 niggers or more didn’t need to fight. He could go home ‘n’ raise crops.

“Jasper Collins was a close friend of mine. When he heard about that law, he was in camp, in the Confederate army. He threw down his gun and started home. ‘This law,’ he says to me, ‘makes it a rich man’s war and a poor man’s right. I’m through.’”

(Jones County, in the southeastern part of Mississippi, had fewer slaves than any other county, only 12 percent of its population. In Newt Knight’s day, all this was a primeval forest of enormous longleaf pines so thick around the base that three or four men could circle their arms around them. This part of Mississippi was dubbed the Piney Woods, known for its poverty and lack of prospects. The big trees were an ordeal to clear, the sandy soil was ill-suited for growing cotton, and the bottomlands were choked with swamps and thickets.)

“Well, I felt the same way about it. So I started back home. I felt like if they had a right to conscript me when I didn’t want to fight the Union, I had a right to quit when I got ready.

“There was about 50 or 60 of us out here in Jones and Jasper counties. Later there was about 125 of us. Never any more.

“We knew we were completely surrounded by the rebels. But we knew every trail in the woods. So we stayed out in the woods minding our own business, until the Confederate army began sending raiders after us with bloodhounds. Then we saw we had to fight. So we organized this company and the boys elected me captain. They elected Jasper Collins first lieutenant and W.W. Sumrall second lieutenant.”

Uncle Newt rocked back and forth meditatively and gazed into the fireplace, where the oak logs were crackling.

“Yes sir,” said he, “there was right smart trouble then. We were pretty quiet for awhile. We figured out that the rebels were too strong for us just then to fight our way through to jine up with the Union forces. And we thought that we’d wait until the Federals fought their way down closer to us or we got stronger. But the rebels started to build a fire under us. I remember the night Alpheus Knight was married up near Soso. That wedding ended up in a battle. Not that I aint’ heard” — and the old man smiled with quaint humor — “that lots of other weddings end up in battles, too.

“Only this was a right smart battle. You see, there was one woman living near us who didn’t like us. She got word of Alpheus Knight’s wedding. He was a cousin of mine. And she told her nigger cook: ‘Gal, you take this message and don’t you stop to eat or sleep until you’ve delivered it to the Confederate soldiers by Ellisville (the county seat). But some folks that were friendly to me, they send word about it.

“Well, Alpheus, he got married all right. It was a right cold night, just durin’ Christmas week. I told ’em to go ahead and celebrate the weddin’, ‘n’ I’d keep watch. There was only less’n a dozen of us there. We kept scattered a lot, so the rebels couldn’t trail us so easy.

” ‘You’ll freeze to death,’ they told me, when I started out to watch the nearest crossin’ on the river. ‘The Lord lights a fire in a man to keep him warm when he’s workin’ for a good cause,’ I told ’em. And I started out. I walked up and down the bank, about a half a mile each way. It was deathly still in the woods. Then just after daylight, I heard a chain rattle on a flat (flatboat). I knew it was the rebels crossing the river. I could hear their horses’ hooves. Then I could sight of ’em. They was about 100 of ’em stomping on that flat. I had about a half-mile to go to the house where Alpheus and his bride were with the rest of us who went to the wedding. I made that half mile right fast.

“When I got to the house the lady had a big breakfast laid out. ‘You’re just in time,’ she told me. ‘Sit down and eat.’ ‘I’ve got no appetite,’ I said. ‘There’s a fight coming.’ They urged me to eat. Finally I ate a little piece of pie and drank some hot coffee.

” ‘Come on,’ I said. ‘We’ve got to get out of here. There’s about a hundred Confederates marchin’ on this house.’ Well, we all packed up and started. There were some ladies there. One of ’em had a baby in her arms. ” ‘I can’t carry this baby so fast,’ she said. So I took the baby.

” ‘I’ll carry your gun,’ she said when I took the baby. ‘No, madame, you won’t,’ I said. ‘Nobody carries my gun but me.’ We hadn’t gone 200 yards from the house when I heard a clatter of hooves. ‘Here they come,’ I yelled. But it was only a passel of critters runnin’ wild. Some colts out in the bush. We all felt easier — and then all of a sudden there were guns going off all over the place.

“About 20 of the Confederates had ridden up behind those wild critters. The minute they saw us they opened fire. That baby clung tighter than ever to me when the guns went off. ‘Here, ma’am, take yo’ baby!’ I told the mother. I had to scrunch down so she could get it. She was a sort of low-built woman. But she got it.

“I swung round to look at the Confederates. There was a captain riding straight at me. A big man, with his head set sort of cross-ways on his shoulders. I can see him yet. I raised my gun. ‘Lord God, direct this load,’ I prayed, and I fired. He tumbled out of his saddle. I looked around the place. We were outnumbered. So I jumped into the brush, and I yelled as loud as ever I could:

” ‘Attention! Battalion! Rally on the right! Forward!’ There wasn’t no more battalion than a rabbit. But there was thick woods all around, and the rebels must have thought there was an army in them. They reined in their horses anyway, and dashed back to the main body. That gave us a chance to get away.”

Again Uncle Newt relapsed into silence.

“Any of your men wounded?” I asked. “Yes, a few.” “Wounded, yourself?” “No — but they did their best. They shot off my hat and powder horn. All we had was muzzle loaders, shotguns mostly. They had these new repeatin’ rifles.”

“Shotguns?” “Oh yes. We got pretty good results, though. I heard one doctor say we must be right smart shooters to hit one man 11 times with rifle bullets. I didn’t tell him we used to use ’bout 18 rifle bullets to the barrel, loadin’ those ol’ percussion cap shotguns. Good ol’ guns. Here’s mine.”

And Uncle Newt brought down from its wooden pegs an ancient weapon. Oiled wood and polished steel were as immaculate as when it came from the hands of the maker more than a half century before. It was a double-barreled twelve-gauge shotgun, muzzle-loading, with twin hammers and nipples for the percussion caps, and a slender polished wooden ramrod down beneath the barrels.

“Sal’s a good ol’ gal,” grinned Uncle Newt as he fondled the weapon, brought it lightly to balance at his shoulder and aimed it at an imaginary bird flying high.

“How’d your company get its powder and lead?” I asked. “Off the Johnny Rebs, mostly,” grinned Uncle Newt. “We got word once of a Confederate wagon train goin’ through Jones County. There warn’t many of us, but we scouted up on ’em and got ’em surrounded. The boys all had big drive-horns. (These were the horns used in rounding up stock, summoning the men to dinner from the fields, driving cattle, etc.) Well, there’d be a big blast up in the woods, to one side. Then another on the other side. Then another in front and one in back. These drivers must have thought we had an army in the woods. Then when we came a-shootin’, they cut and run.

“We got a lot of powder that time, and some lead and a lot of sutler stuff. But we never had much trouble about ammunition. There was a lot of powder and lead in the country stores when the war started. And one widder near us had a piece of lead, about 50 pounds. One of my men was courtin’ her daughter, so of course she gave us what we needed. Th’ ol’ hen flutters when you come round the lone chick, you know?” And Uncle Newt grinned.

“Didn’t you capture a Confederate commissariat base up near Paulding?” I asked, mindful of one exploit of which I had heard in Laurel. “Shucks, that warn’t much of a job,” said Uncle Newt. “Yes, I took the boys up there to Paulding. There was a guard of Confederates over the building. The supplies was all corn. They made out I took right smart other stuff. But it was all corn. I just walked up to the saloon man there and told him I’d shoot him if he gave the boys any whisky before we go the stuff loaded. He didn’t give ’em any.”I remember there was some Irish families there at Paulding. They were pretty bad off. They didn’t want to fight, and the Confederates wouldn’t give ’em or sell ’em anything. I gave ’em all the corn they said they wanted. Then we took the rest back to our headquarters in the woods.”

“Ever run short on food?” “Lord, no,” said Uncle Newt. “There were plenty of deer and wild turkeys in the woods and lots of our friends kept hogs and other stock. We had right smart of friends about Jones and Jasper counties, you know. They helped us a lot. The women were fine.

“I was tellin’ you about the time we scared the Confederates in that wagon train by using big drive-horns. Well, there was one lady I remember, all alone in her house. Some Confederate cavalry, four or five of ’em, rode up to her one day and asked her where her son was. He was one of my company. ‘I don’t know where he is,’ she told ’em. ‘Yes, you know,’ they told her. ‘Now tell us where he is.’ ‘Well, says she, ‘I told you the truth. I don’t know where he is. But I can find out.’

“She took out a big drive-horn and went out on the gallery and blew it. Pretty soon somebody answered with another blast up on the hillside in the brush. Then another blast came from another point. I guess there were ’bout a dozen answers to that horn. That Confederate leader looked at his men. ‘Boys, I guess we’d better get out of here,’ he said. And they sure got.”

(After Vicksburg fell, in July 1863, there was a mass exodus of deserters from the Confederate Army, including many from Jones and the surrounding counties. The following month, Confederate Maj. Amos McLemore arrived in Ellisville and began hunting them down with soldiers and hounds)

“Do you know,” mused Uncle Newt with a whimsical look grin on his face, “there’s lots of ways I’d rather die than scared to death.” Silence again for a few minutes while the ancient splint rocker creaked. “Yes, those ladies sure helped us a lot. I recollect when Forrest’s cavalry came a-raidin’ after us. They had 44 bloodhounds after us, those boys and General Robert Lowry’s men. But 42 of them hounds just naturally died. They’d get hungry and some of the ladies, friends of ours, would feed ’em. And they’d die. Strange, wasn’t it?” A grin of almost school-boyish mischief lit up the rugged old face.

“Them dogs certain had a hard time of it. Some of ’em died of lead poisoning too. And then we’d scatter red pepper on the trails, and pole-cat musk and other things a hound dog loves.”He grinned again.”I’m told that General Lowry caught some of your men,” said I. Lightning-like that grin vanished. In its place flashed a look of bitterness that showed the fires of half a century ago were not all dead, cold ashes.

“He was rough beyond reason,” said old Newt Knight, with sudden curious absence of country dialect in his speech. “He hanged some of my company he had no right to hang.” There’s a story current in Laurel that while Lowry was running for governor of Mississippi he never came into Jones or Jasper counties. That he wouldn’t want to meet you.” Uncle Newt Knight’s face remained granite-hard. “I don’t know about that,” said he.

The clear old voice broke into my thoughts.

“You was asking were we short on supplies,” said Uncle Newt. “We were all fired short on tobacco. Didn’t bother me. I didn’t use it. But it sure bothered some of the boys. I remember one feller in my company. He got some fine navy sweet plug on one raid we was on. There was one youngster was always a-dyin’ for a swet chew. He’d fixed up some chewin’ of part of tobacco ‘n’ part bark, bitter’n gall. ‘N’ he begged this man for some of his sweet navy plug to mix with his bitter stuff.

“Well, th’ ol’ feller was cantankerous. He wouldn’t give up any. He said if he shared with one he’d have to share with all. So he wouldn’t share with any.

“We was a-campin’ by the river one day, a-castin’ lead in bullet molds. This feller who had the sweet tobacco took out a big chew he’d just cut ‘n’ stuck it on the end of a pine branch while he went down to the river to get a drink of water. The youngster was right thar. I saw him slip out his old, bitter chew, pop the sweet one into his mouth, ‘n’ stick the bitter one on the pine branch. Th’ ol’ stingy cuss came back. He reached for his chew.

” ‘Hol’ on,’ said the youngster. ‘That’s my chew.’ ‘The h— it is,’ said the old feller, and put it in his mouth. It made him almighty sick, it was that bitter. When he came to, he jumped at the young feller. ‘I’ll whop you to death,’ he yelled. And he meant it.

“I had to step atween ’em ‘n’ tell th’ ol’ feller that the youngster was right. He’d told him it wasn’t his chew. But that shows how men can get when they can’t get tobacco.”

“How many fights did you have with the Confederate forces?” I asked him. “And how many men did you lose?” Uncle Newt thought for a moment.

“There was a lot of skirmishin’ that you couldn’t properly call battles,” said he. “But we had 16 sizable fights that I remember, and we lost 11 men. I never kept track of how many wounded. I used to treat their gunshot wounds myself. There were a number of them.”

“Many close shaves yourself?” Uncle Newt smiled cryptically. “One or two,” said he. “I remember once when a big fellow was coming at me, and my gun hammer spring wouldn’t work. It was a homemade spring I fixed after the first one broke. He pretty nearly got me.”

Then — “There was once,” he smiled, “when a fellow who was afraid to come out in the open and fight me paid another man to come up and whop me. This fellow who was paid for the job came up, wavin’ a bottle of whisky and inviting me to have a drink. I didn’t drink. He kept waving that bottle around my head. I knew he was looking for an opening to smash me. I kept watchin’ him. I was ready the first move he made. Then he says: ‘Great Good, Newt Knight, don’t you ever wink your eyes?’ ‘Not when I’m looking at your sort of cattle,’ I told him. He judged it warn’t a good day for fighting, I reckon. Anyway, he quit.”

And as he spoke, with those chill, blue-grey eyes staring, Uncle Newt illustrated how his head had followed the motion of that whisky bottle. Ninety-one years old!

But about some details Uncle Newt had naught to say. He lapsed into silence, to speak later on some trivial matter, when asked about the current story that his command had executed at Ellisville a Baptist preacher reputed to have told the Confederates one of his hiding places.

“We never did have any luck,” he said toward the end, “in connecting up with the Union army. I sent Jasper Collins to Memphis as a courier to the Union commander to get us all regularly recruited in the Union army. They sent him to Vicksburg to see General Hudson or Huddleson, or something like that. Then the Federals sent a company to recruit us. That company was waylaid by some Confederates near Rocky Creek. It surrendered.

“Then I sent a courier to the federal commander at New Orleans. He sent up 400 rifles. The Confederates captured them. We just naturally never did connect up with the Union officers and get enlisted regularly. So when the war was over, we just disbanded and went about our business.”

“How many of the company are living today?” I asked. “All I know is seven,” said he. “I keep my old muster rolls out there in the woods in one of my places. Whenever I hear that one of the boys has died, I mark him off on the rolls. Who are the ones left? I’m not tellin’ that. No use namin’ a lot of names and getting people worked up again. When this last war with Germany came along, I called all my folks together and told ’em to do the right thing and get into it. The Civil War’s over long ago. No use stirring up that old quarrel this late day, is there?”

There was cordial farewell; cordial invitation to “drop in again.” At a sign from old Uncle Newt, one of the folks on the place brought out a sack of peanuts from the log storehouse. It was pressed upon us with courtly hospitality — all the gift Uncle Newt had to offer. As we drove away, the gnarled old figure stood erect by the hand-hewn picket fence, waving good-bye.

Records of the Mississippi Historical Society bear out in many details Newton Knight’s story. I am indebted for them to Judge Stone Deavours and to W.S. Welsh of Meridian, as I am indebted to Sheriff W.E. Welsh of Jones County, former Mayor Goode Montgomery of Meridian, Mrs. McWhorter Beers of Meridian, historian of the D.A.R. now writing a history of Jones County, and W.L. Pryor of the First National Bank of Meridian, for many of the local stories current about the Knight Company.

Jones County, named after John Paul Jones, was in 1861 almost a unit against secession. Its citizens elected J.D. Powell, anti-secessionist candidate, to the Secession Convention at Jackson, by a heavy majority, only 24 votes being recorded for J.M. Baylis, the Secessionist candidate. But when the test came, Powell voted for secession. He was hanged in effigy in Jones County, and abused so violently that he did not return within its borders for a long time.

Nevertheless, Jones County responded loyally to the Confederacy’s call for troops. From her scanty population she recruited three full companies of infantry and furnished a great part of four more on her borders, jointly with Jasper, Covington and Wayne counties. They served the Confederate states throughout the war.

When a party of Federal troops set forth from near Brookhaven to destroy the Mobile and Ohio Railroad about Waynesboro, Lieutenant W.M. Wilson of the 43rd Tennessee Infantry was sent to intercept the force. He started with a handful of men. Covington and Jones counties reinforced him with men too old for regular service and with boys too young. By strategy he outwitted and ambushed the Federal band who outnumbered him greatly, killed one, wounded several, and bluffed them into a surrender at Rocky Creek near Ellisville. This is the Union force that Newt Knight says was sent to muster his company into Federal service.

It is now 55 years since the Civil War ended. Yet today many in Jones and Jasper County are reluctant to talk freely of Knight’s Company and the deeds of the times. Scores of descendants of men involved are prominent in that section today. The Confederates’ descendants still refer to Knight’s command as “deserters,” “bushwhackers” and “Jayhawks.”

“No romance in it all all, sir,” said one veteran to me. “Just a bunch of deserters hidin’ out and bushwhackin’. That’s all.” But since 1865, Newt Knight has gone his own way, rarely appearing among city folk. Thrice he has visited Laurel, now a modern city of 14,000 — but almost impenetrable forest and brush when he led his men over its site. He has never ridden in a trolley car, used a telephone or seen electric lights at night. Annually he drives to Ellisville for his simple medical supplies of blue moss, castor oil and calomel. His kinfolk bring him ammunition. He hunts for days, grows garden truck and sells to some friends the axe-helves he shaves from oak trees he cuts himself.

There in the forest he lives, while within him burn fierce memories of foray and pitched battle, mixed with the old, simple pioneer humor. And there in the forest, he says, he will be laid away — when “Taps” sounds for the commander of the company that fought the Stars and Bars in the heart of Dixie, though never officially enrolled with the Stars and Stripes.

“When you grow up in the South, you hear all the time about your ‘heritage,’ like it’s the greatest thing there is,” film director Gary Ross says. “When I hear that word, I think of grits and sweet tea, but mostly I think about slavery and racism, and it pains me. Newt Knight gives me something in my heritage, as a white Southerner, that I can feel proud about. We didn’t all go along with it.”

“In 1875, he (Newt) accepts a commission in what was essentially an all-black regiment,” says Ross. “His job was to defend the rights of freed African-Americans in one of Mississippi’s bloodiest elections. His commitment to these issues never waned.” In 1876, Knight deeded 160 acres of land to Rachel (his second wife), making her one of very few African-American landowners in Mississippi at that time.