Notebooks for Making a Marxism with American Characteristics

How good history makes for better strategy and tactics

By Carl Davidson

One divides into two—This classic phrase for dialectics is a good way to begin this project, with its condensed shorthand for a critical method for studying history, political strategy, and nearly everything else. So it is with ‘USAmerica’s’ long history, from the earliest days to the present. Our country has always contained at least ‘Two Americas’ within its ever-changing boundaries, so I’ll emphasize this and other internal contradictions unfolding in our complex history. First, I’ll start by dividing history from above and history from below. But other methods will be used as well. There are many rich lessons to learn from our revolutionary forebears. Studying other parts of the world is always beneficial, but importing dogmatic models or heroic leaders from abroad is unnecessary.

The somewhat clunky ‘USAmerica’ is occasionally used to indicate that ‘our America’ is one of many ‘Americas’ in this hemisphere. But I won’t always use the term since the point is made upfront. Sometimes, I’ll use ‘Turtle Island,’ the name many Native peoples gave to North America. More important, I use dialectical divisions in subdividing broader populations into the class struggles of what I’ll call the ‘Four Es’–the Exterminated, the Expropriated, the Exploited, and the Enclosed. These are separated and combined in various ways in their battles and other tensions with the distinct upper and overlapping master classes of all of the ‘E’s.’

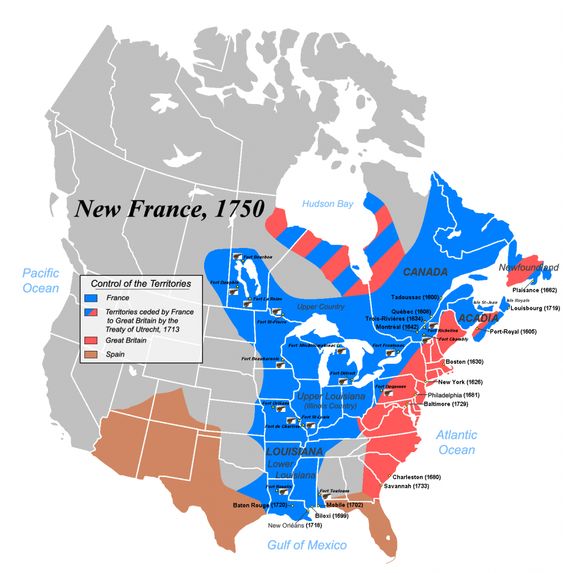

As the label suggests, the Exterminated are all the Native peoples of ‘Turtle Island,’ the name many of them gave to our now-shared North American continent. After the first contacts, no one knows for sure how many were wiped out by European diseases or by slaughter in warfare—a conservative estimate is some 50 million. Apart from direct killings, many mass killings and deaths were indirect, such as trading infected blankets or from the near extermination of the Buffalo herds, a food source for many tribes. A smaller proportion was worked to death as enslaved workers, either on plantations, in the mines, or at sea. The Apalachee in the Southeast all but disappeared from disease. In New France and elsewhere, the settler-colonialists profited from as many as they could in the fur trade, and for those they could not, they killed them or left them to perish by other means.

Two things are certain: the Native peoples never ceased to resist, and they were hegemonic in the homelands for far longer than we are told, and those remaining today, around five million in over 500 tribes, are due a considerable degree of self-determination and reparations to enable their future generations to thrive.

The Expropriated are those captured in Africa, taken from their homes, sold to masters of slave ships, and brought here in chains, at least those who survived the grim Middle Passage, and their latter offspring. By 1705 in Virginia, nearly all African bondservants and their children had been redefined as the permanently enslaved. This meant they produced wealth for their masters ‘in perpetuity,’ save for a relative few who established themselves as ‘free’ workers, small producers, or business owners. As chattel-bond labor, they were exploited for profit in world markets in cotton and other commodities, and they were subjected to torture, abuse, rape, and indignity in the process. As enslaved peoples, they frequently rebelled or escaped to found ‘maroon’ territories with degrees of self-government beyond the reach of their enslavers. Even after emancipation, the Freedpeople suffered a multi-tiered labor market and social exclusion, where their lower tier was segregated by both custom and terror. On the bottom, they resisted and had to be forcefully kept there.

The Exploited were those who came or were brought here, mainly from Europe, to work as indentured servants, only to become ‘free labor’ after five, seven, or twelve-year terms. At least half perished from disease, warfare, or overwork before their terms of indenture ended. So in these years the lives of the simply exploited, in many circumstances, were not that far removed from the enslaved. Once their terms of indenture were up, they were supposed to get a final payment and a bit of land to work, although many never did. They might be kidnapped and impressed as seamen. Or if they could move to a town, they could contract themselves again as an apprentice or journeyman to a master artisan. Many would not see anything close to a decent living as a wage worker or artisan until their contracts were up. European-American workers in East Coast cities were among the first to form the hundreds of small unions that emerged in the antebellum era. Unfortunately, their unions often excluded free Black workers. They likewise held conflicting views on Native peoples and slavery, both North and South of the Mason-Dixon line.

The Enclosed, finally, are all those peoples who have had the U.S. draw its borders around their countries, territories and regions, whether for shorter or longer terms. Think of Puerto Rico, the Philippines, Guam, American Samoa, and Hawaii, and well as the remaining Native peoples on their ‘reservations.’

Varieties of Class Struggle

All four of the ‘Four E’s. ’ nonetheless, had much in common with each other in waging a common class struggle against their various masters. In certain conditions, all four categories were worked and exploited together, such as those who made up the ‘motley crews’ of ships at sea or Cortez’s use of enslaved Natives, Blacks, and even Native free wage labor to work his silver mines in what is now Mexico. As seamen, the ‘motley crews’ often did combine to improve their lot and sometimes even seized the ‘floating factories’ for themselves, striking out as pirates. In New Sweden, settlers tried a co-op version of socialism. Quakers, Native Peoples, and escaped slaves intermarried and formed a democratic ‘Albemarle republic’ for a few decades in North Carolina. Enslaved and free African workers, European and European-American workers intermingled in New Netherland’s New Amsterdam, now New York City. In large part elsewhere, however, their lives were separate—African slaves labored on isolated plantations, Native peoples worked in the fur trade or remote mines, and the formerly indentured, given a new identity as ‘white,’ made their way to the workshops in the towns or tried to get a bit of land on ‘the frontier,’ the regions bordering Native lands or lands held by Spain or France.

The Four E’s often found themselves in contradiction—poor Europeans working as overseers or patrollers for the enslavers on their plantations or as ‘frontier ‘scouts’ driving Native peoples from their lands. Or the colonized people of Puerto Rico or Guam. Native peoples, for their part, often ‘adopted’ runaway or captured Africans (and Europeans) into their tribes and families. But they also held them as enslaved people for themselves or as war booty for sale or trade to others. For 200 years or so after the ‘first encounters,’ the European settlements were only a string of small coastal or river towns, often fortified. But they subsisted in a vast sea of indigenous hegemonies, large and small. One Native people, the Comanche, held off the Europeans for more than 150 years.

After the Civil War and Reconstruction, expanding capitalists often employed African Americans as strikebreakers against European-American labor trying to organize or waging strikes. In these cases, some of the latter ‘white’ workers got a ‘repayment’ of defeat for excluding Blacks from their unions. A few times, the reverse happened, where white workers were hired as strikebreakers against Black workers. The racialized divisions and identities held them all down, whatever status or privileges were imposed. Next Page

Class and Democratic Struggle via Historic Blocs

Class struggle in the U.S., then, has rarely taken any pure form of ‘class against class.’ Instead, we find it often taking the form of ‘historic bloc vs. historic bloc’ in wide varieties. The use of this ‘bloc’ terminology was first deployed by Antonio Gramsci, who had borrowed it from the French syndicalist Georges Sorel and reworked it to understand Italy. Gramsci’s initial concern was giving birth to an alliance of Northern Italian workers with the ‘subaltern’ peasants of southern Italy, Sicily, and Sardinia. (Of course, the working class is also a subaltern in relation to the capitalist class).

In our context, the blocs of subalterns can include or exclude any of the ‘Four E’s’ or several or all of them in various combinations. Enslaved people rising against enslavers is a class struggle, even when European-American wage workers fight on the wrong side. Likewise, Native peoples found themselves aligned with Black labor, free and enslaved, against the settler colonialists. Nor do these blocs lose their class character when they are joined by small farmers, other middle-class elements, or even, at times, sectors of the bourgeoisie.

Any given worker or set of workers in this setting rarely exhibited anything like ‘true’ class consciousness. Because we find this ‘true’ qualifier objectionable, as we also reject the flip side of the term, ‘false consciousness.’ Marx never used this ‘false consciousness’ concept, the use of which puts one on a slippery path to elitism and metaphysics. Again, one divides into two. Our consciousness is best seen as conflicted, as a social self that starts with a tension, at a very early age, between the ‘I’ and the ‘me’ (tipping our hat here to George Herbert Mead, who founded social psychology in the 1930s by developing these concepts). The ‘I’ is a dynamic psychic element, reflecting on one’s experience and making efforts at change. The ‘me’ is the more passive ‘generalized other,’ which is first a long and ever-changing narrative reflecting on the ways we perceive how others may be perceiving us. The’ me’ includes all the stories we learn growing up—our family histories, our religious practices (or lack thereof), and the national folklore learned in schools and churches.

In short, our self-consciousness is a hologram of all the conflicted and contentious identities and narratives of the old order, or as Karl Marx called it in ‘The German Ideology,’ ‘all the old muck.’ But in addition to identity and narrative, our consciousness is also shaped by social structures. Most important is our relation to production—as a purchaser of labor, as purchased labor, or as labor trying to purchase itself. In the world of work, we also learn skills for effective production, we learn to work cooperatively, and we learn many new ideas about science and history.

‘All the old muck’ in our divided consciousness is what Gramsci called our ‘common sense,’ meaning ‘ideas widely held,’ not our American meaning of practicality. What we learn in science and the workplace, Gramsci calls our ‘good sense.’ The work of revolutionary pedagogy aiming for social change toward a new order, then, requires the development of ‘good sense’ as a means to engage and subdue ‘common sense.’ It entails mobilizing any positive factors to reflect upon practice and change, isolate, or discard negative factors. Herein lies the method of developing revolutionary class consciousness on a micro level.

Why does this matter? Simply put, without understanding our consciousness as conflicted, we can make little sense of our history’s full and deep dimensions. To change their world at different times, The ‘Four E’s’ needed to know who they were and where they stood in relation to potential allies and adversaries. (‘Who are our friends, who are our enemies,’ is how Mao Zedong posed the first question of strategy (‘Analysis of Classes in Chinese Society,‘ 1926). They also needed a vision of who and what they might become. ‘All the old muck’ was used to hold everyone down. Learning its flaws thus enabled them to throw off old and backward ideas and emancipate their minds.

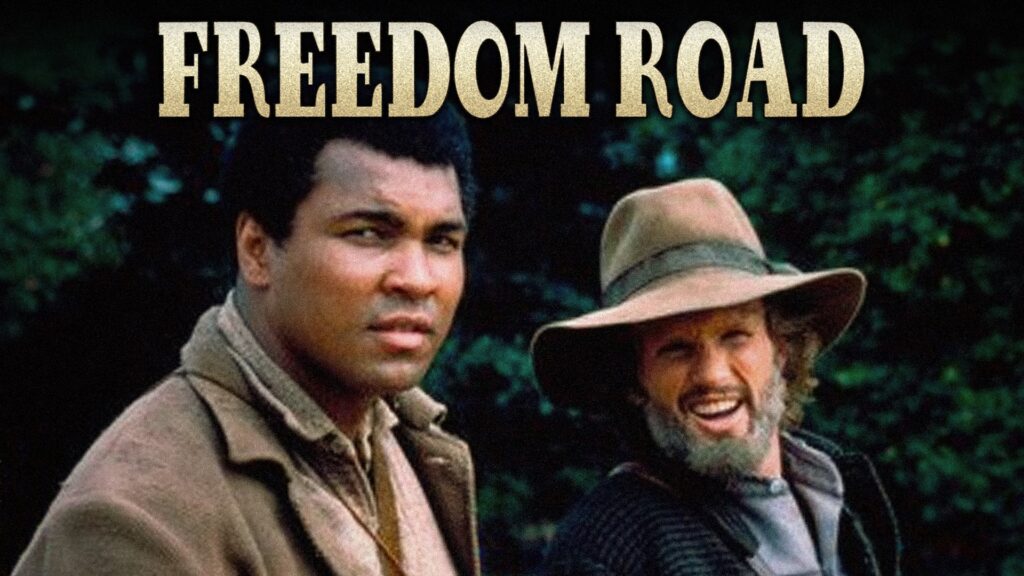

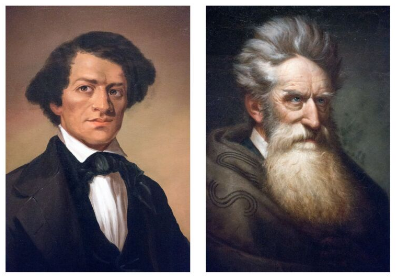

Muhammad Ali and Kris Kristofferson as Freedman and Scalawag partners in Black Reconstruction movieThe Subalterns in Power

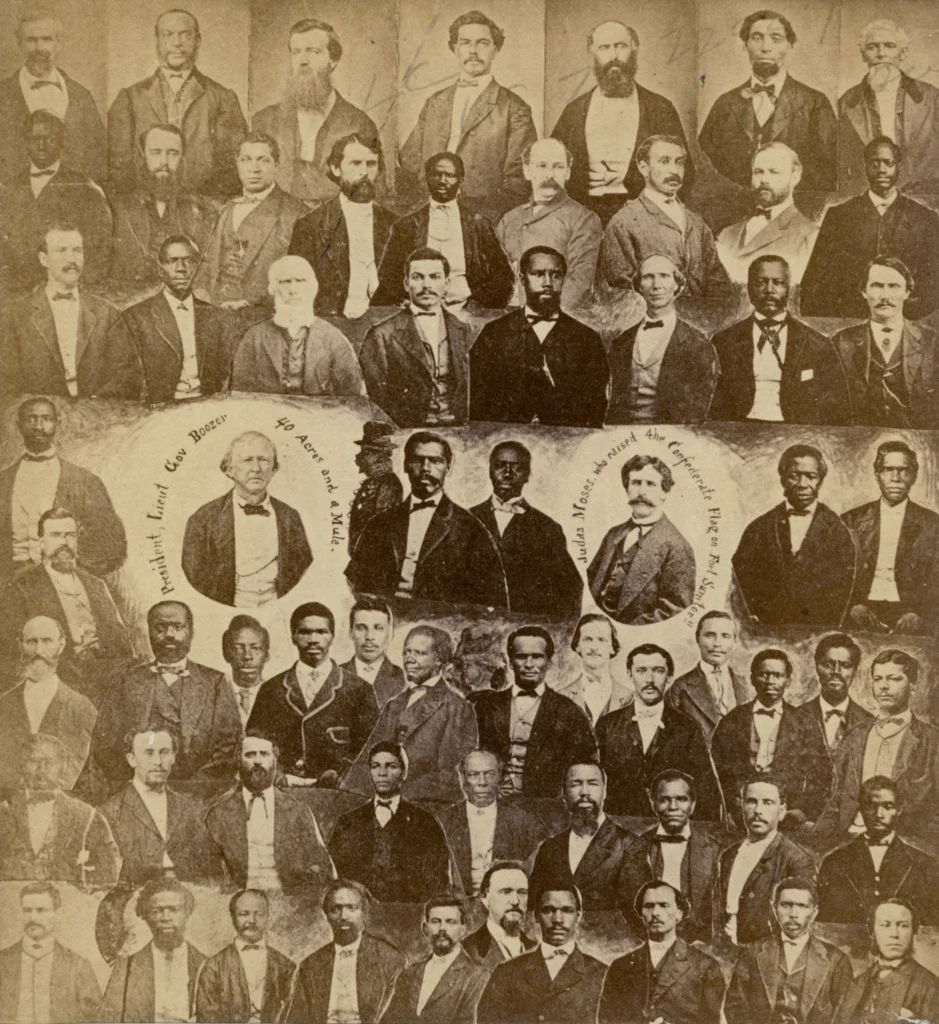

The early and pivotal example of an insurgent bloc of subalterns in contention for state power was the Reconstruction governments in some 10 Southern states from 1865 to 1877 (None lasted the whole period). These were best seen as democratic republics of working people with Black freedmen at the core, but closely allied were more than a few pro-Union Southern ‘scalawags’ or ‘poor whites.’ The emerging political consciousness of this insurgency was that of radical abolition democracy and more, especially the demands for breaking up or taking over old plantations in favor of independent Black ownership, Black-owned collectives, or black-and-white cooperative farms. Not many of these got off the ground or lasted long. But Blacks went on through the ‘Jim Crow’ era to form a wide variety of ‘survival coops’ lasting from the First Reconstruction all the way to today’s ‘solidarity economy’ projects in Jackson, MS, and elsewhere.

In our time, the most recent insurgent bloc was the massive elemental rising against the white supremacist injustice inflicted on George Floyd in Minneapolis. It was a class struggle at its heart, even though some sectors of other classes than the rainbow working class joined it, while some sectors of the workers abstained or opposed it. We can argue that these upheavals were, in various ways, both class and national-democratic struggles. But consciously or not, they were taking up Marx and Engel’s concluding instruction to us in The Communist Manifesto, that the path to socialism for the working classes comprised engaging and winning all the battles for democracy. Next Page

A Fresh Look at Our History

Our history is many-sided. From North America’s earliest days–from the 1619 selling of slaves in Virginia, or the 1620 landing of Europeans at Plymouth Bay occupying Native homes vacated earlier by European disease, or the 1570s French fur trade setting tribe against tribe in Quebec, or the slave revolts of the late 1700s in Haiti, the purging of the Tuscarora from the Carolinas, or the 1680 Pueblo revolt in New Mexico—all of these had an impact in shaping what would become ‘USAmerica.’ The oppressed and the exploited rose in rebellion against the ruling blocs of their oppressors and exploiters. Sometimes they fought alone; other times, they formed blocs with others. Most of the time, they lost; but in a few cases, they won. Sometimes their victories lasted only for a short time, but in a few others, they lasted longer. But there was never a time when Turtle Island wasn’t contested terrain.

Why do we need a new national narrative? First, we need the tools to fight the GOP’s current efforts to rewrite history once again. Much anti-white supremacist history we added to our schools in the 1960s is under attack today in over 20 state governments, largely in the Old Confederacy but reaching outward as well. Second, we need to make a new and more accurate consciousness of ourselves, our past, and our future. The recent ‘1619 Project,’ organized and primarily written by Nikole Hannah-Jones for the New York Times, redated our beginnings as an American people from that year. She was widely criticized and scolded for not using 1776. But her date is as good as any and better than most. (One wonders if she would have met with the same resistance had she picked one year later, 1620).

But the main point many of her critics opposed was her bringing to the surface a little-known fact. For some Anglo-Americans fighting for Independence, mainly Southern ‘planters,’ their main concern was defending slavery. (I put ‘planters’ in scare quotes because the enslaved did nearly all the planting). Since slavery had been outlawed in Great Britain proper (but not yet in its colonies), a victory for the British, they feared, might mean the spread of abolition to its American colonies, as it had in Canada. We can argue over the degree to which various actors had these mixed motives, but not that they were nonexistent.

What can’t be disputed is that tens of thousands of enslaved Africans joined the contending blocs of both sides in this conflict. Those are matters of fact. Nor can it be disputed that of the Loyalist Bloc (about 20 percent of the English colonists), some 60,000 headed for Canada when they saw British defeat coming, if not before–and that many Africans, enslaved and free, escaped with them.

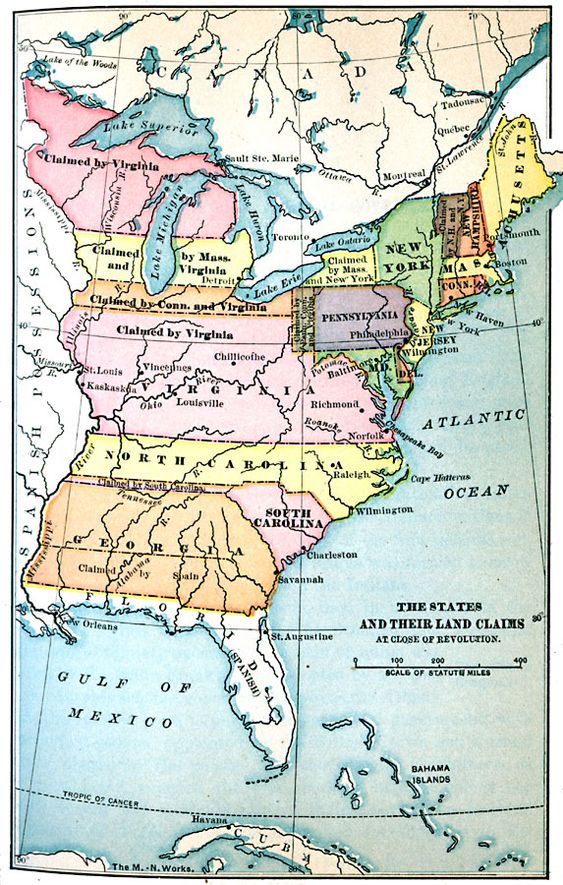

Likewise, among the Native peoples, the Haudenosaunee (or ‘Iroquois,’ a derogatory French term) sided with the Americans. But many others, such as the Shawnee, sided with the British. In both cases, the Africans and the Native peoples were gambling on how best to defend their interests against the new and expanding settler-colonial slave republic. In the case of the bloc of the Shawnee and their allies under Tecumseh, they waged battles for a common Red homeland in the early Northwest Territory. These efforts continued beyond the 1789 Constitutional Founding until the War of 1812 when Tecumseh was finally defeated and killed in 1814 in Canada.

The ‘settler-colonial slave republic’ of the USA, with this linked chain of descriptors, is obviously conflicted as a political entity. Early in 1780, Thomas Jefferson named it an ‘Empire of Liberty,’ envisioning its expansion to the Mississippi River and even absorbing Canada. However, he was taken aback and fearful of the 1803 Haitian Revolution. He worried that it might spread, via New Orleans, then owned by France, to the slaves of the South. After the ‘Whiskey Rebellion’ in Western PA, he worried about efforts to form a breakaway ‘Western Mississippi Republic’ (Aaron Burr was involved in such a plot). It’s why Jefferson sought and obtained the Louisiana Purchase from Napoleon in 1803, who desperately needed cash for other projects, especially fighting Spain.

At one master stroke, Jefferson had doubled the territorial claims of the new nation to all lands drained by the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers, reaching to the ‘Stoney Mountains,’ as he called them. The 1804-1806 Lewis and Clark Expedition–part scientific, part military—surveyed the various peoples who lived in the vast region, taking stock of their military abilities and other resources. Jefferson was rather explicit that the Natives must be displaced or confined. Given their hegemony in their various homelands, the only question was how it might be done.

Despite their grandiose claims to vast swaths of territory on maps, Europeans controlled only a few dozen port cities or river villages with a few hundred troops. Faced with Tecumseh’s rising in 1812, Jefferson arrogantly told John Adams, “These will relapse into barbarism and misery, lose numbers by war and want, and we shall be obliged to drive them, with the beasts of the forest into the Stony mountains.” Next Page

The Empire of Liberty Expands

The expanse of the ‘Empire of Liberty’ was loosely defined by Jefferson. He never quite grasped what was on the other side of the Rockies and had relatively flexible ideas about this side. In 1804, he said: “I confess I look to this duplication of area for the extending of a government so free and economical as ours, as a great achievement to the mass of happiness which is to ensue…. Whether we remain in one confederacy, or form Atlantic and Mississippi confederacies, I believe not very important to the happiness of either part.” In 1809, he sent a note to James Madison: “…We should then have only to include the North [Canada] in our confederacy…and we should have such an empire for liberty as she has never surveyed since the creation: & I am persuaded no constitution was ever before so well calculated as ours for extensive empire & self government.”

Jefferson’s close assistant in arranging the Louisiana Purchase was James Monroe, who later, in 1816, became the 5th President of the U.S. Monroe first served as a diplomat in Europe, and initially supported the French Revolution. He was also a slaveholder known for treating his slaves harshly and often selling them to clear his debts. He directly felt the impact of ‘Gabriel’s Rebellion’ in 1800 in and around Richmond, VA. When it was suppressed, he saw to it that Gabriel and 25 other rebel enslaved people were hanged. Despite this, he often claimed to oppose slavery as an economic trap imposed on the country by Great Britain in the colonial period. Near his death, he wished he and other enslavers could send the enslaved back to Africa after being compensated for their loss by the federal treasury. But he never did anything to oppose slavery’s persistence, save for helping to initially draft the Northwest Ordinance, which excluded slavery in the Northwest Territory, and reluctantly signing the Missouri Compromise, which, except for Missouri, banned slavery above 36′ 30″ latitude.

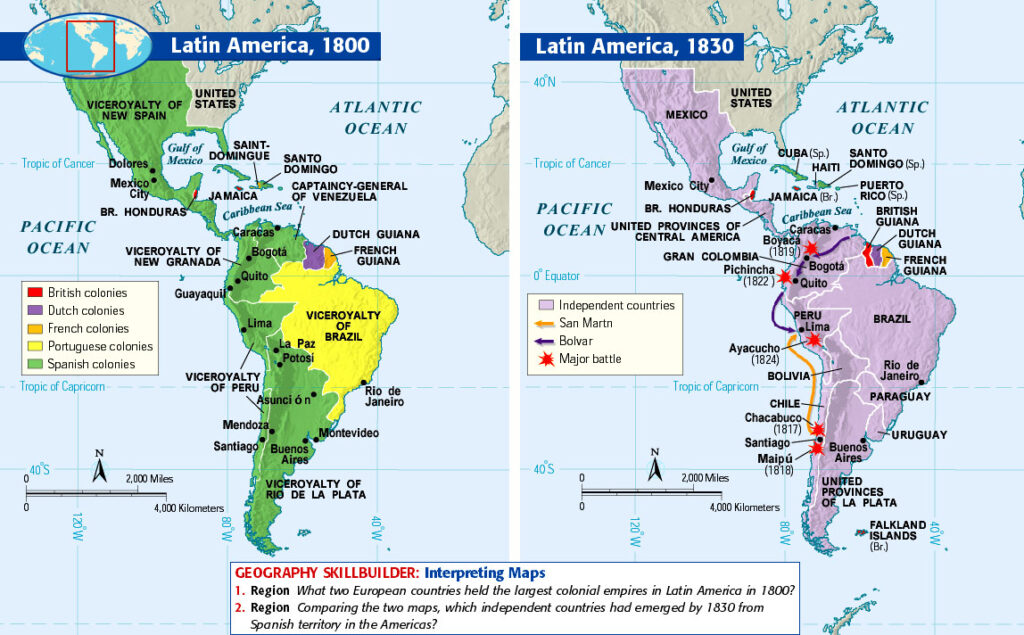

Monroe was said to have had two great political fears. One was a class insurrection of the poor laborers, which he witnessed in the ‘excesses’ of the French Revolution. The other was a racial and servile insurrection, which he saw in Richmond and through his knowledge of the Haitian revolution. At the same time, in a conflicted consciousness, he held the wars for independence (and slave abolition) across Spanish America, primarily led by Simon Bolivar, in a favorable light.

Monroe Expands the ‘Empire of Liberty‘

Monroe was most interested in opportunistically taking advantage of Spain’s difficulties to seize Spanish Florida. He sent Andrew Jackson to take most of it militarily, waging war with the Seminoles, who were joined by the escaped slaves who lived with them, and with Spanish troops. Spain finally gave up all of Florida in a treaty, which they hoped giving up the East would better define and secure the western border of New Spain in Mexico and the Southwest. Next Page

Bolivar and the Spanish Collapse

James Monroe helped to shape and redefine Jefferson’s ‘Empire of Liberty’ globally. He pledged to keep the U.S. from intervening in European affairs while insisting that no European power could intervene to thwart the Bolivarian revolutions in the New World. (This did not apply to colonies in the hemisphere that had not yet revolted, such as Cuba, British Honduras, and a few others in the Caribbean and South America). It wasn’t called ‘The Monroe Doctrine’ then, but it held into the future for better or worse. We can see it as the root of the ‘superpower mentality’ that we suffer as a ‘common sense’ burden weighing us down, especially today.

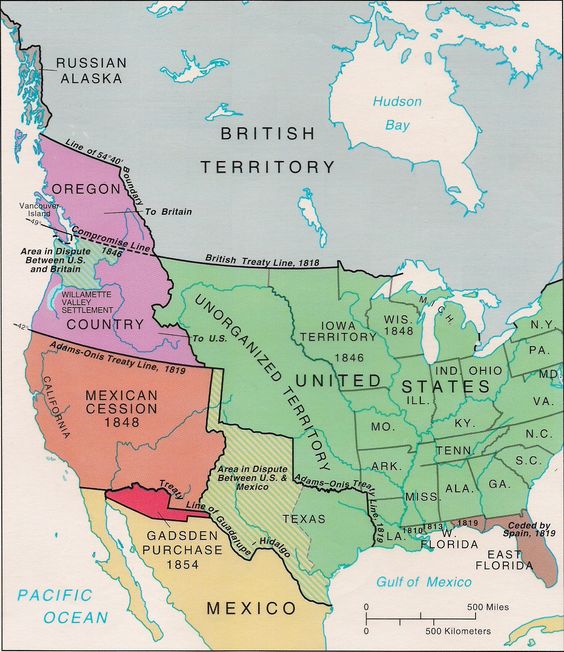

Monroe and Bolivar were contemporaries, both dying in 1830. In their prime political years, they were both allies and rivals. The conflict within the upper classes over the nation’s future was finally taking shape in the U.S. itself. One divides into two again. One side was expansionist, seeking conquest of everything south of 36’30” latitude. A line set by the Missouri Compromise; it was also a border above which cotton could not be easily grown. In addition to the western areas south of the line, the ‘King Cotton’ enslavers also had their eyes on Cuba, Mexico (which reached up to the Oregon country at the time), and what is now Central America. Internally, this first side also wanted all lands in the Southeast, such as Georgia and Alabama, using ‘ethnic cleansing,’ i.e., driving all Native peoples to the western side of the Mississippi, as in Andrew Jackson’s ‘Trail of Tears.’

Divisions at the Top

The other side of those of the U.S. American elites elected to Congress was more cautious for various reasons, good and bad. Some Congressmen wanted normalized relations with Native peoples, granting a degree of autonomy and national or tribal rights, along with respect for Spain and then Mexico’s borders in the West. It’s worth noting that Andrew Jackson’s enabling legislation for Native Removal passed Congress by only one vote.

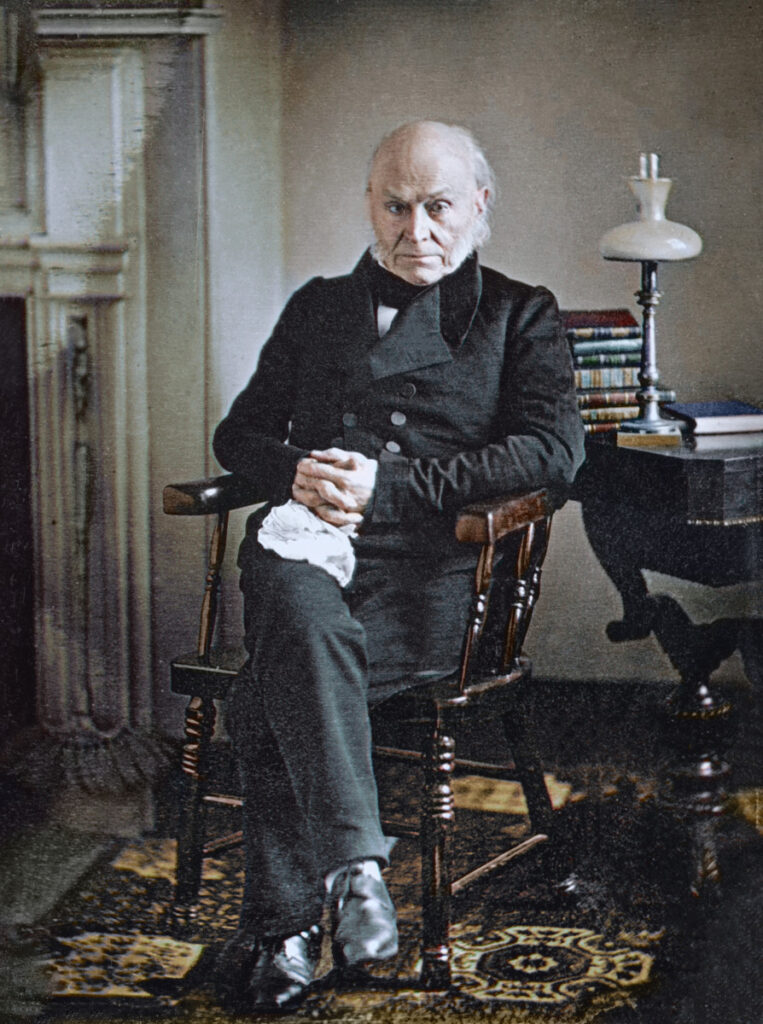

This mainly Northern faction, primarily represented by John Quincy Adams, also prefigured what would later become linked blocs of both citizen-based abolitionism and mass opposition to the U.S. War on Mexico. The Adams–Onís Treaty, negotiated with Spain in 1819 by John Quincy Adams, as Monroe’s Secretary of State, secured both Florida and a path through the Midwest to Oregon. Still, it established a firm border with Spain west of the Sabine River in Texas. When Mexico won its independence, the same Spanish border was still acknowledged, at least for a while.

The new hegemonic term, ‘ Manifest Destiny, ‘ grows out of this tension between the two ruling blocs, with the Jacksonian white supremacist popular bloc gaining the upper hand. It was coined in 1845 by John L. O’Sullivan, editor of the political magazine, The Democratic Review. Some have argued that it was coined by a writer and editor he employed, one Jane Cazneau. The editorial concerned was unsigned but consistent with her writing, which she often left unsigned. Women writers were often ignored or dismissed in those years. In any case, the term took on a power of its own, and ‘Manifest Destiny’ is now taught to all American students as a defining national quality. Next Page

The Texas Two-Step: How the Slavocracy Took Over

Since the 1830s, many enslavers had eyes on the fertile land across the Mississippi known as Texas, first as part of Spain and then Mexico. Some wanted to expand their plantations there to gain more profits. Other plantation owners were more stressed, and bankrupted in a cotton crisis. Rather than face confiscations by creditors, they packed up their slaves and equipment and hung a sign on the plantation’s door, stating ‘Gone to Texas, ‘ Spanish territory.

Mexico, which had become independent of Spain in 1824, initially welcomed U.S. settlers to the Texas region, but not without conflict. By 1829, Mexico had abolished slavery, and its ongoing practice was illegal in all their territories. Many new Texas immigrants from the U.S. were not slave owners, but many were. Making slavery legal became the root cause of the quest for independence waged by the new Anglo-Texas immigrants. The independent ‘Republic of Texas’ was first declared in 1836 and lasted ten years until its annexation by the U.S. in 1846. Mexico never recognized the claim of Texan Independence and considered the region a rebellious province, whether ‘independent’ or a U.S. state.

‘Manifest Destiny,’ then, was born and asserted with the annexation of Texas and the drive for war with Mexico. The presidential campaign of James K. Polk in 1846 saw Mexico’s annexation and called for taking California, all of Oregon, and much of the rest of Mexico. Polk’s continent-wide plans for the United States, to be taken by any means necessary, was the substantial meaning of Manifest Destiny. He first tried to buy California and everything in between from Mexico for $25 million, which Mexico refused. Polk’s aims were also opposed within Congress, where a Northern grouping saw Texas as a slave territory, giving a numerical majority in Congress to the slave states and thus sinking the Missouri Compromise.

Polk starts the war

Mexico claimed the Nueces River as its northern border, although the Republic of Texas had claimed the Rio Grande. Polk took advantage of the dispute to send U.S. troops across the Nueces and into Mexico, engaging its forces. The fight was on, and Polk called for a declaration of war, falsely claiming Mexico had invaded the U.S. and killed American troops. An initial wave of Manifest Destiny jingoism got the approval of Congress, but not without opposition. Henry Clay and several others, including a young Abraham Lincoln, newly elected to Congress from Illinois, opposed the war. As the war’s cost and casualties grew, a relatively large and powerful antiwar movement emerged. Winfield Scott’s armies entered Mexico City, ending the fighting but without an immediate settlement.

Polk had wanted to take all of Mexico but soon saw additional opposition from Southern quarters for their own reasons. The slaveowners feared for the future stability of a single expanded country with too many resident peoples of color, including those in a country where slavery had been abolished. Ultimately, the U.S. annexed Mexico north of the Rio Grande, less populated than the southern half. All Spaniards, Mexicans, and Native peoples living in the northern half thus became American subjects without citizenship rights. California, with a relative handful of 28,000 American settlers and soldiers, briefly declared the California Republic, but it quickly became a ‘free’ state to balance the slave state of Texas. With the discovery of gold in 1848, California’s population grew quickly, but land grabbers wiped out most of the Native peoples simultaneously.

In 1846, the U.S. also settled the Oregon border with the British at the 49th parallel, setting the area up as a defined U.S. possession, officially proclaiming it a territory. Oregon residents in 1844 had declared themselves a territory free of slavery, but uniquely. They banned not only slaves but all Blacks from any settlement. Oregon was eventually named a ‘free’ state in 1859, in exchange for opening the other former Mexican territories of the Southwest to slavery. In the same period, the Mormons migrated en mass to the ‘Great Basin’ area of former Mexico and started their own state, ‘Deseret,’ later to become Utah.

Thus Manifest Destiny was complete, with the continental U.S. stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Any celebration, however, was to be short-lived. By 1861, the U.S. saw one dividing into two again. Nearly all the slave states declared their succession from the Union and formed the Confederate States of America as a white slavocracy. Next Page.

Slavocracy and the ‘Irrepressible Conflict’

The pressures leading up to the Civil War were building up for decades–beginning with ongoing slave rebellions and enslaved people escaping via the Underground Railroad, most leading Northward, but some also leading to Mexico. The Northern states, one by one, outlawed slavery within their borders. Naturally, Abolitionism among the slaves and free Blacks had always existed, from their capture in Africa to David Walker’s 1829 Appeal and beyond. Among European-Americans, abolitionism emerged before Independence as a moral and religious movement, beginning with Quakers in 1688 and again peaking in the 1730s through the efforts of Benjamin Lay, who as a seaman, also gave a proletarian caste to his Quaker religious arguments.

It wasn’t until 1776 that the Quakers entirely forbade holding or selling slaves by anyone in the Society of Friends, the Quaker’s actual name. The colony of Rhode Island was the first to abolish slavery in 1652. The colony of Georgia, designed for European ex-convicts, initially banned slavery in 1733 but reversed itself in 1751. Vermont rejected slavery in 1777, when it was still an independent polity, and remained so after joining the U.S.

The question of slavery was debated at the Continental Congress in 1775. Anti-slavery provisions appeared in the first draft of the Declaration of Independence, probably due to Jefferson or perhaps Thomas Paine, who wrote powerfully against it in 1775. Here’s the extracted passage:

“He [King George] has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life and liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating & carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither. This piratical warfare, the opprobrium of infidel powers, is the warfare of the Christian King of Great Britain. Determined to keep open a market where Men should be bought & sold, he has prostituted his negative for suppressing every legislative attempt to prohibit or restrain this execrable commerce. And that this assemblage of horrors might want no fact of distinguished die, he is now exciting those very people to rise in arms among us, and to purchase that liberty of which he has deprived them, by murdering the people on whom he has obtruded them: thus paying off former crimes committed again the Liberties of one people, with crimes which he urges them to commit against the lives of another.”

The passage was removed at the insistence of Southern delegates. Pennsylvania soon saw the first anti-slavery society, followed by gradual, then complete abolition in the commonwealth. Other Northern states followed suit. Beginning in 1790 through 1830, the ‘Second Great Awakening,’ a religious revival and mass upheaval largely involving women of all classes, spread throughout the North and often included the abolition of slavery as a key tenet.

It can be noted here that the masses of women, in their own way, should also be considered as part of ‘the Expropriated.’ Not only was this due to their wageless service to men in patriarchal families—many women among still matriarchal Native peoples were not—but also due to the growing practice of sending young unmarried women into textile mills by their fathers. The fathers then collected their daughter’s wages, leaving the young women only a tiny allowance. In brief, European-American women had reasons of their own for their pro-abolitionist rising in solidarity with the enslaved.

William Lloyd Garrison is credited with being the first ‘white’ national voice for abolition through his newspaper, The Liberator (1831-1865). By its first publication date, a majority in the North opposed slavery in one form or another. However, Garrison and his newspaper were noted for clarity on the call for immediate abolition everywhere, on the one hand, and the call for ‘moral suasion,’ nonviolence, and the avoidance of electoral politics as the means to do so, on the other hand. Garrison also opposed the U.S. Constitution as a ‘pact with the Devil’ and deemed it impossible to reform. His gatherings were soon joined by Frederick Douglass, an escaped slave, a writer, and an eloquent speaker with direct experience with slavery, and very successful at growing the impact of The Liberator.

Douglass gradually differed from Garrison on the Constitution, on arms use for self-defense, and on electoral politics. In 1847, he published his own newspaper, The North Star. He collaborated closely with Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, John Brown, Gerrit Smith, Martin Delany, and Henry Garnet—all leaders in what might be called a multiracial left-wing of abolitionism. Douglass also took part in the women’s rights campaign launched in 1848 at Seneca Falls, N.Y., and did much to encourage early feminism.

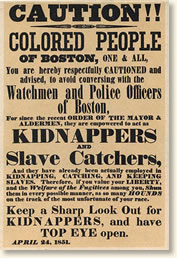

However, the state laws at the time could not do away with the fugitive slave provisions within the U.S. Constitution. Southern slave catchers were ‘within their rights’ to apprehend escaped slaves in the North and return them to their masters. With the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, Northern citizens were also required to assist in these captures or face heavy fines and prison sentences. This measure served to spur the growth of the abolitionist movement.

The division between the abolitionists and much of the rest of the relatively new nation was very deep. Again, one divides into two. For the abolitionists, Blacks were ‘brothers’ in common humanity, regardless of any degraded status. For the rest of ‘White America,’ citizens were overwhelmed by various ‘scientific race theories,’ rooted in flawed studies of cranial size, shapes of skulls, and other pseudo-science hypotheses and data. Continually created and revised to justify Black slavery, these widely publicized views had become hegemonic in universities and civil society. Many argued for ‘plural genesis,’ meaning there was no common root ancestor of whites and Blacks. One theory argued that Blacks stood at the pinnacle of the Ape family, while whites were a separate creation by God in Adam and Eve. Noah, then, acted properly in herding Blacks onto the Ark with other animals to serve him and his offspring as they saw fit.

Charles Darwin’s concurrent discoveries opposed all this. But his revolutionary work was nonetheless soon distorted and undermined by a different reactionary theory of ‘Social Darwinism,’ which argued for white supremacy as a product of ‘survival of the fittest.’ The abolitionists, then, faced not only economic, military, and political battles but deep ideological and cultural battles as well.

If abolitionism was the political left in the late 1850s, the center was composed of the Whigs, including politicians and lawyers like Abraham Lincoln. Their politics was to oppose the further spread of slavery outside the South and some designated territories in the Southwest. Lincoln himself held complicated views on slavery. He often asserted his personal opposition to slavery but had conflicted political views. On the one hand, he held to what he saw as ‘natural law’ in the Declaration of Independence and thus held that all Blacks were entitled to ‘Life, Liberty, and Property.’ On the other hand, Lincoln held to the ‘positive law’ of The Constitution, which allowed for slavery, unless amended or restricted, as in the Northwest Ordinance. As for civil rights generally, he initially opposed them but later came to support them. After conversations with Douglass and other free Blacks, he grudgingly gave up his ‘colonization’ views, the idea of removing all Blacks to Africa or Latin America.

But the critical question of the day was opposition to slavery’s expansion. Its implications especially led to sharp divisions between Northern and Southern Whigs, leading to the party’s implosion and collapse in the late 1850s. Lincoln’s Whigs had to regroup with the Greenbacks, Free Soilers, the small abolitionist Liberty Party, and others to form a new party, the Republicans. With Lincoln’s nomination, a mass youth movement of workers and farmers, the Wide Awakes, emerged from Massachusetts to Illinois to support his campaign. They organized colossal nighttime torchlit marches in cities and towns across the region. The combination of all these groups and clusters meant the GOP stood at the center of a new rising counter-hegemonic bloc to the slavocracy.

While some in the North may have believed containment would allow Southern slavery to endure indefinitely, the enslavers held no such illusion. They knew slavery had to expand or die. The world market constantly demanded more cotton; other places, such as Egypt and India, were rising as competitors. Slavery’s cotton-growing methods also had a hard impact on the soil, always requiring new acreage to come under cultivation. Some Southern enslavers even argued for expanding into the North, bringing white wage labor in the textile and other mills into chattel bondage. Thus within months of Lincoln’s election, the Southern states were seceding, and South Carolina opened fire on Fort Sumpter. Next Page

Unleashing a New Revolution

The Civil War started as an effort to put down a rebellion against the Union, and many in the North may have viewed slavery as secondary. Many soldiers at first, with mixed views about slavery and some disdain for Blacks, did not see themselves as abolitionists. But Karl Marx and Frederick Engels were quite lucid on the matter and argued for a deep understanding of the revolutionary character of the war that would soon arise. Under Marx’s byline, they wrote a hundred or more articles appearing in the main Northern newspapers, explaining much of the political economy of slavery and its impending crisis. Their followers in the U.S., immigrant German socialists and communists for the most part, quickly joined the Union army and recruited others to do so.

Opposition to the slavocracy had other enemies within than German socialist immigrants in border regions like Missouri. Within the Deep South, in thickly wooded or hilly areas unsuited to cotton, those without slaves resented secession and voted against it. These ‘Unionists’ also resisted conscription into the CSA army or deserted. They staked out pro-Union counties, declaring their own independence from the CSA. The most famous of these was ‘The Free State of Jones,’ which lasted throughout that war and into Reconstruction. (A recent Hollywood movie rescued the story from the memory hole).

The region that eventually became the state of West Virginia separated from Virginia and aligned with the Union during the Civil War. West Virginia was admitted to the Union in 1863 and played a significant role in the conflict. The decision to split from Virginia was driven by various factors, including economic differences and pro-Union sentiments among the region’s residents. While not as pronounced as West Virginia, parts of eastern Tennessee were also known for their pro-Union sentiment, and several counties in the region actively opposed secession. The region experienced a significant internal conflict as Unionists clashed with Confederate sympathizers, and the area was under military occupation for much of the war.

It soon became apparent to Lincoln, his GOP supporters, Frederick Douglass and the abolitionists, and Lincoln’s best generals that victory required, first, the emancipation of the slaves and, second, the recruitment of Black soldiers into the Union armies. The 13th Amendment came first, while Lincoln was still alive, soon to be followed by the 14th, guided by Thaddeus Stevens and the Radical Republicans, and the 15th under President Ulysses Grant.

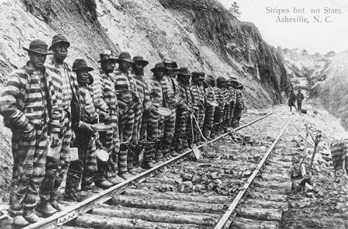

As with the Declaration, it’s worth looking a the first draft of the 13th Amendment: “All persons are equal before the law, so that no person can hold another as a slave; and the Congress shall have the power to make all laws necessary and proper to carry this declaration into effect everywhere in the U.S.” As we can see, it lacks the loophole in what was later adopted, a loophole that caused much grief later on: Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

After Lincoln’s assassination, President Andrew Johnson attempted a sham reconstruction. He quickly tried to bring the old CSA elites back into power, with their effort to rule paired up with ‘Black codes’ that re-subjugated Blacks to the state of slavery in all but name. The Radical Republicans, however, were 75% of the House. Led by Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania, they saw to it that Congress quickly rejected the seating of any Southern delegations of this sort. The GOP then passed a Civil Rights Act and overrode Johnson’s vetoes. The 14th Amendment was also passed, establishing citizenship for all born or naturalized in the jurisdiction of the U.S. (The Dred Scott decision thus bit the dust). Its ratification was required by any former CSA state seeking a return to Congress.

The Radical Republicans then moved to impeach Johnson on various charges, which passed in the House. However, a guilty verdict in the Senate required a two-thirds vote, and Johnson escaped by a margin of one vote. One reason he may have squeaked through was the fear by some in Congress that his next-in-line successor would be Benjamin Wade, President Pro-Tempore of the Senate. Wade was not only a stalwart Radical Republican but also a strong trade unionist, equal rights for Blacks advocate, and supporter of women’s rights. Wade was the far left in Congress.

In 1865, prominent Black abolitionists met in upstate New York and formed the National Equal Rights League. Spreading rapidly to other Northern states, the NERL reached beyond abolition to begin the all-around advocacy for the ballot, equal rights, and economic reform at the core of Radical Reconstruction. But again, one divides into two. William Garrison took a different course and ceased publishing The Liberator in December 1865, asserting its work was done. He also tried to dissolve the American Anti-Slavery Society for the same reasons but failed. Frederick Douglass joined the NERL, and Wendell Phillips continued advocacy of Reconstruction, adding the importance of land reform—’40 acres and a mule’- for the Freedmen.

Thus, the ‘Reconstruction Amendments’ and the support of the ‘Freedman’s Bureau’ enabled the rise of Black-led, interracial worker democracies in the South during the post-Civil War era. Approximately 2,000 Freedmen were elected to various public offices in over ten states, ranging from local sheriffs to U.S. senators, and had pro-Union Southern white workers and farmers as allies. These ‘poor whites,’ labeled as ‘scalawags’ by former Confederates, were about 20% of white voters. The legislation passed during this time, known as Radical Reconstruction, remains some of the most progressive legislation in Southern history to this day.

However, the Ku Klux Klan and other extremist groups, calling themselves ‘Redeemers,’ launched violent campaigns and lynchings to overthrow Radical Reconstruction. In response, the Black-led governments organized their own armed forces from Black veterans of the Civil War and received assistance from U.S. troops stationed in the South. President Ulysses S. Grant ordered troops to oppose the use of violence against Blacks trying to form new governments.

In the wake of our bloody national Civil War, then, a second civil war immediately unfolded across the South to reverse the verdicts of the first. Once more, one divides into two. The two contending political blocs were the White Redemptionists, anchored in the former enslaver class, on the one hand, vs. the Multinational Reconstructionists, anchored in Black laboring people and their white Unionist allies, on the other hand. The Freedmen and poor whites also had other less reliable allies in the North.

Reconstruction shamefully was not supported by emerging labor unions in the North, which excluded Blacks as ‘competitors for our jobs.’ Nonetheless, the defense of these governments entailed a deep class struggle of a political character, and the two primary contenders have been locked in an ongoing struggle to the death, to one degree or another, to this day.

However, the decline of the Radical Republicans during Grant’s second term and the rise of the moderate ‘Liberal GOP’ and Northern Democrats led to a lack of interest in defending Freedmen political rights and civil rights. The controversial 1876 election, where the GOP’s Rutherford Hayes ran against Democrat Samuel Tilden, was challenged since neither got a majority of Electoral College votes. (The outcome in a few Southern states was contested). The result was a brokered but informal deal (a betrayal in many eyes) in which Tilden agreed to concede in favor of Hayes in exchange for withdrawing all federal troops from the South. This arrangement allowed ex-Confederates, the ‘planter’ class, and their paramilitaries, including the KKK, to seize power and launch prolonged repression. It marked the beginning of ‘white redemption’ and the ‘Jim Crow’ era. Next Page

White Redemption Continues into the 20th Century

With the codification of Jim Crow laws, sharecropping peonage, enslavement in ‘chain gangs’ for ‘vagrancy,’ and the 1898 ‘Plessy vs. Ferguson’ ‘Separate but Equal’ decision, the White Redeemers did away with Black voting and ruled by lynch law from 1877 through the 1940s.

1898 also saw the onset of the Spanish-American War, and the conquests in the Caribbean and the Pacific. The US was now more than an Empire within its continental borders. It now spanned the globe’ with colonies in the Philippines and elsewhere in the Pacific Islands.

The

Spanish-American War of 1898, though brief, erupted like a thunderclap that

reshaped the course of history. What began as a fiery debate over Cuban

independence soon spiraled into a conflict that thrust the United States onto

the world stage, transforming it from an internal continental conquest into an

imperial force with global reach.

Yet

beneath the triumphant headlines of “Remember the Maine!” and the roar of

patriotic fervor, a quieter storm of dissent brewed at home—a chorus of voices

questioning the cost of empire and the morality of conquest.

After winning

in the Caribbean, the U.S. Navy obliterated Spanish fleets in Manila Bay and

Santiago, and secured victories that stunned the world. The Treaty of Paris

handed America a portfolio of overseas territories: Puerto Rico, Guam, and the

Philippines. As we noted above, many of these are included in our ‘4th

E,’ ‘The Enclosed.’ Victory over Spain marked the dawn of a new era. Newspapers

like William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal celebrated the nation’s

ascent, framing expansion as a divine mandate.

But not

all Americans cheered. A coalition of writers, labor leaders, and activists

recoiled at the contradiction of a republic built on liberty subjugating

distant lands. The Anti-Imperialist League, founded in 1898, became a rallying

point for dissenters. Mark Twain, its most biting critic, lambasted the

hypocrisy of “civilizing” Filipinos with bullets, quipping that the U.S. flag

should be painted with “skull and crossbones.” Industrialist Andrew Carnegie,

appalled by the abandonment of isolationism, offered $20 million to buy

Philippine independence—a gesture Spain had rejected for Cuba, now echoed

ironically by an American tycoon.

George

Boutwell — a seasoned statesman and former Secretary of the Treasury under

Presidents Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant — rang out with moral clarity

on the war. A founding member and chairman of the Anti-Imperialist League,

Boutwell brought decades of political experience to the fight against

annexation, framing his opposition in constitutional and ethical terms. He

denounced the acquisition of the Philippines as a betrayal of America’s founding

principles, arguing that governing foreign populations without their consent

violated the very idea of republican government. “To hold and govern distant

communities by force is repugnant to the theory of our institutions,” he

declared, warning that imperialism would corrupt democracy at home.

Antiwar

resistance took many forms. In Boston, protesters flooded Faneuil Hall,

decrying the betrayal of American ideals. The Springfield Republican

warned that imperialism would corrupt democracy, while labor unions feared

colonial exploitation would undercut domestic wages. African American leaders,

keenly aware of the irony, noted the paradox of “liberating” Cubans while Jim

Crow laws entrenched racial violence at home. “Until our nation is just in its

own borders,” argued journalist T. Thomas Fortune, “it cannot pretend to

justice abroad.”

The

Philippine-American War (1899–1902), a brutal coda to 1898, exposed the dark

underbelly of expansion. Filipino revolutionaries like Emilio Aguinaldo, once

allied with U.S. forces, now faced American troops in a guerrilla war that

claimed over 200,000 Filipino lives. Reports of atrocities—burned villages,

water torture—reverberated stateside, galvanizing anti-war sentiment. Poet

William Vaughn Moody captured the disillusionment in An Ode in Time of

Hesitation, questioning whether the nation had “sold its birthright for a

mess of brass.”

Boutwell’s

influence extended beyond rhetoric. He penned scathing essays, including The

Crisis of the Republic (1900), which dissected the legal and moral dangers

of overseas expansion. His arguments resonated with constitutional scholars and

educators, many of whom joined the anti-imperialist cause. Boutwell also

testified before Congress, urging lawmakers to reject the Treaty of Paris and

its territorial annexations. Though his efforts ultimately failed to halt

ratification, his legal critiques forced proponents of empire to grapple with

awkward questions about citizenship, rights, and the limits of executive power.

Domestically,

the war reshaped politics and identity. The Navy’s meteoric rise as a global

force cemented militarism in policy, while the rhetoric of “Manifest Destiny”

evolved to justify overseas dominion. Yet the anti-imperialist movement, though

outmatched, left an indelible mark. It forced Congress to debate annexation

fiercely and sowed seeds of skepticism that would bloom during later

interventions in Latin America. The Platt Amendment, which granted the U.S.

control over Cuban affairs, became a symbol of imperial overreach—a policy even

some State Department officials privately deemed unsustainable.

By 1902,

the war’s legacy was etched in contradiction: a nation straddling its mythos of

freedom and the reality of empire. For every senator proclaiming America’s duty

to “uplift” the tropics, there was a Twain mocking the

“Blessings-of-Civilization Trust.” The conflict had birthed a superpower but

also a conscience, a tension that would haunt U.S. foreign policy for decades.

As the 20th century unfolded, the ghosts of 1898 lingered—in the Philippine

struggle for sovereignty, in Latin American revolutions, and in the enduring

American debate over what it means to wield power in a fractured world. The

Spanish-American War did not merely change history; it revealed the fault lines

of a nation forever torn between its ideals and its ambitions.

Eugenics as reinforcement of White Rule at home

The first decade of the 1900s also saw the government-backed extension of ‘scientific racism’ and ‘Social Darwinism’ by a newly emerging ‘eugenics’ movement. Eugenics, a newly minted term derived from ‘well-born,’ posited hierarchies of intelligence based on race and within races, based on class differentials. Soldiers entering the army for WW1 were subjected to extensive ‘IQ testing,’ designed to sort out, from the bottom up, idiots, imbeciles, morons, and then the rest of the upper working, middle, and ruling classes.

‘Morons’ was a dubious term newly invented for this testing and was applied to at least half of the working class of any race. But ‘moron’ was applied mainly to immigrants from southern and eastern Europe and Blacks, Chicanos, and Native Americans. Even a majority of Jewish immigrants were dubbed ‘morons.’ Determining ‘intelligence’ by a single number that was hereditary (two falsehoods), with a single stroke, not only held down people of color, but held down most of the ‘white’ workers as well. As social policy, apart from sterilization, eugenics aimed to ‘reform’ education so no money was ‘wasted’ on enabling young people of the laboring classes to rise above the conditions of their parents. Instead, all the subalterns would only get provisions for limited literacy and other menial skills.

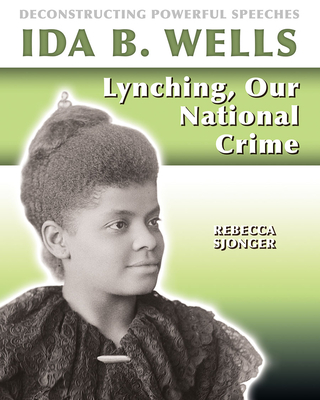

But even when subordinated, at the turn of the century, the popular First Reconstruction forces waged ongoing battles—the founding of the NAACP by DuBois, the Ida B. Wells campaigns against lynching, the interracial worker insurgencies of the IWW into the 1920s, the Black and white sharecropper unions in the 1930s, and many of the labor campaigns of the CIO as well, to name a few. The Freedpeople in the South and the Free Blacks of the North also saw critical economic changes. White Redemptionists cracked the whip and waved the noose to keep Blacks chopping cotton, making railways, digging coal, and producing steel. But capitalism in the North also actively recruited Southern Blacks to draw them into various manufacturing industries.

The Great Migration as resistance

Many Blacks saw the lures to the North as a better offer. At some risk, they began what came to be called ‘the Great Migration,’ with millions of Black families moving to the Northern industrial centers from Boston and New York to Detroit and Chicago. Among other things, this migration changed the Black class structure of Northern cities in a significant way, with the expansion of a Black proletariat, alongside an expansion of urban Black middle classes–small businesses, professionals, and intellectuals. This growing educated elite began to seek its own voice. It was born after slavery and tasted Reconstruction, but Jim Crow still held it down. Next Page

The Black Elite’s Efforts at Resistance and Survival

Starting in 1892 and running through 1938, the Black educated elite began using the term ‘New Negro’ for itself. It first appeared in the Cleveland Gazette, which, at the same time, stopped referring to itself as a ’Black’ newspaper in favor of ‘African American.’ The ‘New Negro’, in short, represented a departure from the old, subservient stereotype of Black people as docile and content with their oppressed status. Instead, the term emphasized Black pride, self-respect, and the quest for equality and justice.

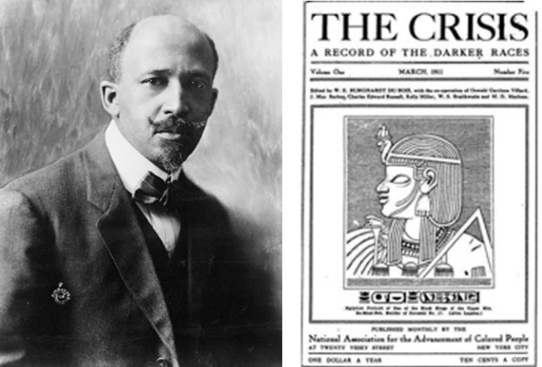

This emerging outlook also went through the ‘one divides into two’ process. First, Booker T Washington, on the right side, in 1900, published A New Negro for a New Century, a collection of essays promoting his views on economic self-improvement. On the left, two voices emerge. Second, in 1916-1917 on the left, Hubert Harrison founded the New Negro Movement in Harlem, with ‘The Voice’ and ‘The New Negro’ as his publications. Harrison connected the struggle for black emancipation with socialism and strongly opposed U.S. entry into WWI. He also worked with Marcus Garvey’s Pan-Africanist movement. Also on the left was W.E.B. Dubois, who strongly opposed the ‘accommodationist’ views of Booker T. Washington and launched the NAACP, along with its magazine, The Crisis. (DuBois stumbled on the war question, advocating for Black enlistment with the belief that their displays of patriotism and bravery would lead to greater rights on their return. It didn’t happen. In fact, on their return, many Black soldiers saw increased lynching and pogroms by the KKK, sometimes just at the sight of them in uniform. In later years, DuBois expressed his regret for this blunder).

In the 1920s, Alain LeRoy Locke jumped into this intellectual turmoil. He was perhaps the country’s leading Black intellectual, with a Ph.D. from Harvard and the first African-American Rhodes scholar. At Oxford’s Hertford College, he studied classics, got a Ph.D., and went on to the Humboldt University of Berlin, where he studied philosophy. On his return to the U.S., he taught at Howard University for many years.

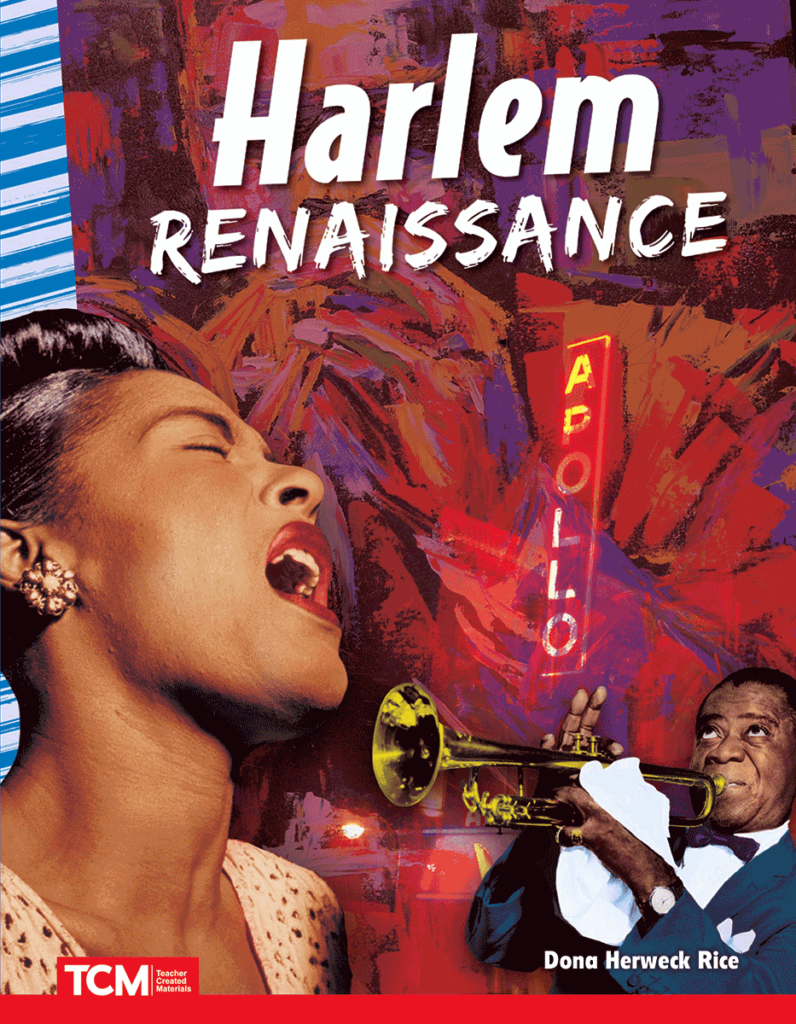

In 1925, Locke was the guest editor of the periodical Survey Graphic, for a special edition titled ‘Harlem, Mecca of the New Negro.’ He expanded the issue into a book, The New Negro, and the broader movement around it emerged as the Harlem Renaissance, which began in 1918 and ran into the late 1930s. The Harlem Renaissance saw an explosion of Black arts, music, literature, and politics. It was the core of ‘the Jazz Age’ of the 1920s. It nourished, along with the ongoing work of DuBois, poets like Langston Hughes and fiction writers like Richard Wright, and musicians such as Louis Armstrong, Bessie Smith, Billie Holiday, and Duke Ellington.

In 1917, another ‘New Negro’ publication appeared in Harlem, The Messinger, founded by A Phillip Randolph and Chandler Owen. The magazine was affiliated with the Socialist Party and several young but growing unions. The war and the Russian Revolution saw a division within the left between the Socialists, critical of the Russian Bolsheviks, and a newly emerging set of Communist parties. Randolph joined Debs in opposing the war but did not join the communists. As the Socialists began to fade, he directly joined in several trade union organizing efforts, starting with elevator operators and other jobs where Blacks were concentrated. His greatest success was the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, where he became president in 1925.

All these figures comprised a wide and somewhat conflicted Black intelligentsia. The Harlem Renaissance, then, can best be viewed along Gramscian lines, with both ’organic intellectuals’ like Harrison and Randolph, and ‘traditional intellectuals’ tied to the academy like Alain Locke. WEB Dubois, with his ‘talented tenth’ theory, where the rise of the most advanced would pull up all or most of the rest, was a bit of both. Next Page

The Communists and ‘The Negro National Question’

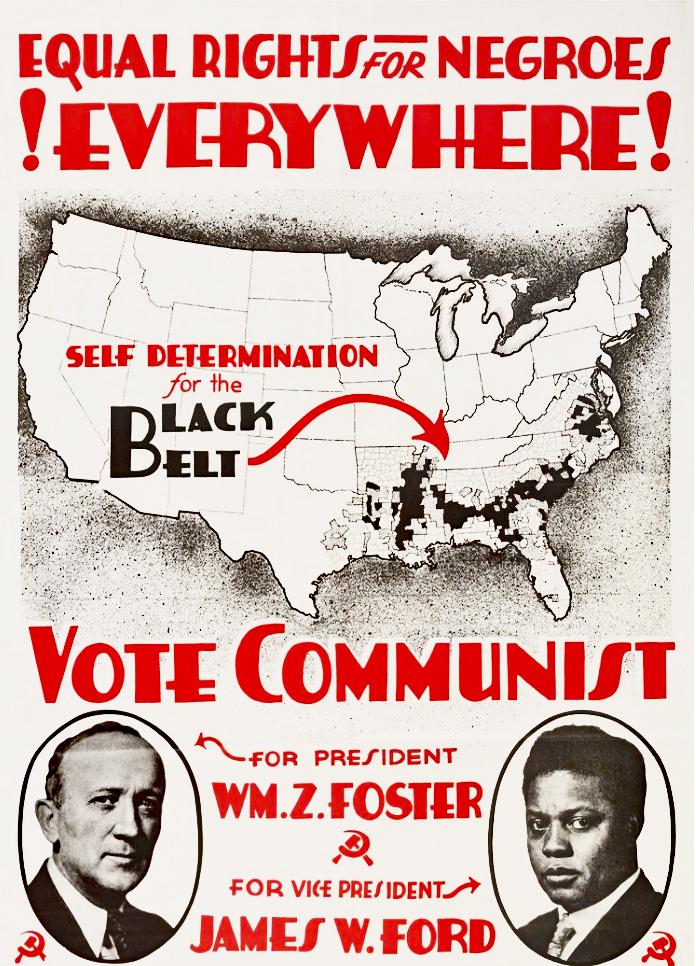

What was the forward path for the communists? From 1918 to 1920, they originally formed two small parties, the Communist Party and the Communist Labor Party. But by 1921, they merged into one at the insistence of the Moscow-based Communist International or Comintern. Several young African Americans, many WWI vets, formed the African Blood Brotherhood, and many of its members joined the communists. A group of these was sent to Moscow to study at the Comintern schools for several years. While there, they engaged with Zinoviev and others to develop a new theoretical approach to African Americans.

By the 1928 or 6th session of the Comintern, a resolution drafted by Harry Haywood was adopted, advocating the position that Blacks in the U.S. were an oppressed nation in the South and an oppressed minority nationality elsewhere, with a right to self-determination and full equality. As a result, the early 1930s saw communists organizing Black and white sharecroppers into unions in the Black Belt, a mass demonstration in Chicago, led by Blacks, against Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia, and a major legal case defending the Scottsboro Boys (nine young Southern Blacks framed on rape charges). These new practices and a ‘new theory’ saw many Blacks joining the CPUSA rather than the Socialists. (It should be noted, however, that viewing Blacks as a ‘nation within a nation’ was neither new nor firstborn in Moscow. It reached all the way back to the Black abolitionist David Walker’s 1829 Appeal and several indigenous affirmations in the U.S. after Walker).

With the onset of the Great Depression in 1932, FDR and his ‘New Deal’ came into power. It meant some gains for labor in the ability to organize and some for Blacks as well. The Civilian Conservation Corps construction camps may have been segregated, but they still offered employment to young Blacks. With the ‘Solid South’ of White Redemptionists in charge, Blacks and Chicanos were primarily excluded from many New Deal worker benefits. The South in Congress, for example, forced the exclusion of agricultural and household workers from social security and unemployment insurance. In many ways, the early New Deal was ‘affirmative action for whites.’ The union organizing drives, and the ongoing cultural expressions of the Harlem Renaissance, still kept the Reconstruction trend alive while subdued overall.

But a significant intellectual event of the decade was the publication in 1935 of W.E.B. DuBois’s masterpiece, ‘Black Reconstruction in America,’ which refuted all the lies of the ‘Deming School’ of history and D. W. Griffith’s film, ‘Birth of a Nation,’ a 3-hour celebration of the White Redeemers that played in every theater in the country, and for many, it was the first movie they ever saw. The pro-Confederate ‘Deming School’ of history held sway in the universities. Unfortunately, DuBois’ book was not widely reviewed at the time. Instead, its adversary arose in the form of a more modern and technicolor spinoff of ‘Birth of a Nation’ in the 1939 film, ‘Gone with the Wind,’ based on Margaret Mitchell’s bestselling 1935 book of the same title. On this cultural terrain, the White Redeemer stories maintained their hegemony.

With the outbreak of WW2, the question of Black troops in a segregated army and fair employment in defense industries once again pushed against the ‘Solid South’ and its Jim Crow restrictions. The African American Pittsburgh Courier editorialized for what it called ‘The Double V Campaign,’ or victory against fascism abroad alongside victory against Jim Crow at home. The Chicago Defender and other Black papers picked up the campaign, and the ‘Double V’ symbol appeared in Black businesses and churches across the country. A. Phillip Randolph and Black unionists started planning for a wartime ‘march on Washington.’ Randolph called it off, however, when FDR promised a fair employment policy, which was widely implemented. With FDR’s death and Henry Wallace’s defeat in 1948, it fell to President Harry Truman to continue these efforts and start desegregating the U.S. military. Next Page

The 2nd Reconstruction Breaks Out

March in Mississippi, 1966

The tensions of the 1940s persisted into the 1950s, despite the rise of McCarthy and anti-communism. By 1954-55, a 2nd Reconstruction finally emerged. After hard-fought legal battles waged by Thurgood Marshall, the Supreme Court rendered the ‘Brown vs. Topeka’ decision desegregating schools. This was followed by the 1955 Montgomery, Alabama bus boycott and the Freedom Rides and sit-ins across the South. This time the events were dramatically broadcast on television, giving them far more impact than radio and print. These campaigns went through several additional upsurges, especially peaking in August 1963 with the March on D.C. and MLK’s famous ‘Dream’ speech. The new movement finally won, under LBJ, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

By 1970, however, these gains were met with a white backlash. The 2nd Reconstructionists were violently set back earlier by the murders of Malcolm X, Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr, and Black Panther leader Fred Hampton. With the murder of MLK, Blacks rose in rebellion in more than 100 cities. The FBI’s COINTELPRO program responded by instigating killings, repression, and political trials against many others.

Realignment in the two parties

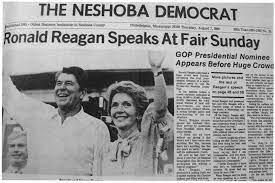

Concurrently, most Southern Redemptionists and their white allies nationwide began to leave the Democratic Party. Following Nixon’s ‘Southern Strategy,’ the segregationists briefly backed George Wallace but ‘realigned’ under the GOP tent, accelerating significantly with Reagan and continuing through Trump in 2016.

Reagan backed this backlash and crackdown by launching his victorious 1980 presidential campaign in Neshoba County, Mississippi, the site of the murder of three civil rights workers. Reagan ignored their fate while speaking a mass events in the area. But he pledged his support for the ‘state’s rights’ platform that reached back through Strom Thurmond’s Dixiecrats to John C Calhoun’s antebellum affirmation of slavery as a ‘positive good.’

In the Reagan years, the 2nd Reconstructionists persisted from below. The Harold Washington campaign won the Mayor’s post in Chicago in 1983, and Jesse Jackson ran ‘Rainbow Coalition’ campaigns for President in 1984 and 1984. While he didn’t win the nominations, Jackson’s several statewide victories reminded other Democrats that the 2nd Reconstruction forces could only be ignored at their peril. The Democratic party and the GOP had been realigned significantly, and major adjustments were in order. Next Page

A Third Reconstruction for Today

Two Reconstructions are behind us. But the point of this extended essay is that the politics shaping both sides remain with us today, at least in their main contours. We need to look harder if we can’t see them at first. We can conclude with a summary of what faces us now and beyond.

The deep economic crisis of 2008-09, one of the most precarious in our history, allowed a Third Reconstruction to arise. It first assembled as a political force in the Obama coalition and grew for eight years, spurred on by the assassination of Trayvon Martin and other outrages. Thwarted narrowly by the Trump backlash in 2016, it gathered strength again after several more police killings, now more widely opposed under the banner of ‘Black Lives Matter.’ The public police lynching of George Floyd set off elemental risings that were massive and multinational class and democratic battles, among the largest in our history. The clear demands were against white supremacy, patriarchy, and the NeoConfederate fascism of the Trump-led White Redemptionists.

The Jan 6, 2021 insurrection as a battle between two blocs

While Biden narrowly won in 2020, the ongoing expression of Neoconfederate Redemption could be seen with the South’s CSA battle flag carried into the halls of Congress during the Jan 6, 2021 attempted coup. This symbolism of the far right reveals the current ‘culture wars’ as two battles—one reactionary, one progressive– over how to recreate and project our American identity as well as to advocate competing political platforms. It shows why we must redefine and express our new narrative and its strategic ideas using the American idioms found within this deep dive into our history. To get where we want to go, we need to know who we are and where we’ve been.

“We here highly resolve,” declared Abraham Lincoln in closing his Gettysburg Address, “that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

Lincoln’s “new birth of freedom” was at the heart of a redefinition of ourselves as a people. That ‘rebirth’ emerged within the Civil War and blossomed in the short-lived Reconstruction governments–our Paris Communes. It didn’t stop there, which is why we also need to awaken to the long ‘War after the War,’ (1865-1920).

The ‘Lost Cause’ campaign for white supremacist ideological and political hegemony enabled the South to win politically what it had lost militarily. It was also an armed conflict across the South between the ex-Confederate Redeemers of lynch law and white order, on the one hand, and the biracial power of the Black South alongside all workers and their allies in several states, on the other hand. The First Reconstruction, lasting until 1876, had the backing of federal troops and its own armed militias. These grew from the Black regiments in the Civil War and the Unionist whites in the South who deserted and/or took up arms against the Slave Power. (The ‘Free State of Jones’ in Mississippi is a well-known example. But less well known are the Reconstruction state militias, with the one in Louisiana organized and led by the former CSA General James Longstreet, who went over to the side of Reconstruction, among several others).

If people today want to uphold revolutionary class unity and struggle, along with the cross-class nature and need for common fronts, this is one place where they can find inspiration. Ongoing examples continue to be uncovered and redefined through all three Reconstruction efforts at taking power. These national-popular blocs were always counter-hegemonic, transformative, and had success in varying degrees. We can best be seen as their descendants, standing on their shoulders and keeping our eyes on the prize.

Our strategic task today, then, through both a ‘war of position’ and a ‘war of movement,’ is to bring the Third Reconstruction into the position of the ruling national hegemonic bloc. First, we develop our strength in labor and community organizations at the grassroots level. We will see that political clout reflected in Congress with the growth of the Justice Democrats and the Congressional Progressive Caucus. It should be evident that the ‘Squad’ in the House and Bernie Sanders, John Fetterman and a few others in the Senate are our immediate pathfinders in Congress. There are more in state-level governments. Any arguments for attempts to break with them or undermine them at this conjuncture with ‘third party’ options are wrong and need to be sidelined and defeated.

Second, we will widen the front by winning over all the centrist forces we can. If we can’t win governmental posts ourselves, we can work to elect antifascist candidates who can win. Then third, we must defeat, scatter, and crush the modern NeoConfederate Redemptionists. Sometimes this will also require direct action or the ‘war of movement’. In doing this, we are ‘winning the battles for democracy’ all along the line.

Taken together, these campaigns will also, as The Communist Manifesto urged us, ‘take care of the future within the present’ and ‘the whole as well as the part.’ Within the Third Reconstruction, we can develop the common ground for refounding a new socialist bloc aiming to rule the country in a new order. Our core strategic alliance comprises a multinational working class and the allied subalterns of all the oppressed and exploited (of which labor is but one). We can follow through from that position by building the green shoots of a socialist reconstruction already underway in several locales and launching many more deep structural reforms on our socialist path forward. Everyone willing to fight is welcome, whether for the whole thing or part of it. But prepare to lead, follow or get out of the way