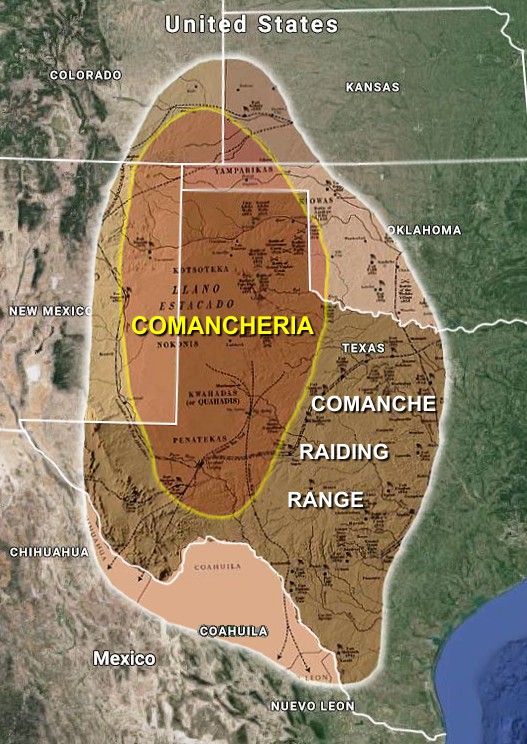

The Comancheria or Comanchería was a region of New Mexico, west Texas, and nearby areas occupied by the Comanche from the 1770s to the 1870s. The Comanche were a nomadic Plains Indian tribe known for their horsemanship and warrior culture.

Understanding the Comanche and other ‘horse tribes’ requires a deeper look at these animals’ social and economic impact. Horse history in North America is fascinating and spans several millennia. Horses were not native to the continent recently but were reintroduced by Europeans during European exploration and colonization.

Horses were absent from the Americas for thousands of years before European contact. The ancestors of modern horses originated in North America but became extinct 10,000 years ago. This was likely due to climate change and overhunting by early human populations.

Spanish explorers and conquistadors reintroduced horses to the hemisphere in the 16th century. In 1493, Christopher Columbus brought horses on his second voyage, and subsequent Spanish expeditions brought more horses to the Caribbean and Mexico. Pizarro took horses to Peru in South America.

As explorers and settlers moved northward, horses spread across North America. Some horses were lost or abandoned, while others were deliberately released or traded with Native American tribes. Horses soon became an integral part of Native American culture, transforming their way of life. The horse, along with the rifle, revolutionized their productive forces.

Horses profoundly impacted Native American tribes in the Great Plains region. Tribes such as the Comanche, Sioux, Cheyenne, and Crow embraced horsemanship and adopted a nomadic lifestyle centered around hunting bison on horseback. This use of horses dramatically altered their mobility, warfare tactics, and trade networks.

The horse revolutionized buffalo hunting on the Plains. Tribes that previously relied on foot-based hunting methods could now pursue bison more effectively, increasing food supply and population growth. Horses allowed tribes to cover longer distances, carry larger loads, and engage in more efficient communal hunts.

A Means of Resistance

The horse-mounted Plains tribes also significantly challenged European expansion into the American West. Native Americans’ superior horsemanship and guerrilla warfare tactics led to long-standing conflicts with settlers and the U.S. government. Famous battles and resistance movements involved horse-mounted warriors, such as the Battle of Little Bighorn and the Ghost Dance.

Today, many Native American tribes maintain solid equestrian traditions. They participate in rodeos, horse racing, and cultural events celebrating their horsemanship skills.

Horse reintroduction also had far-reaching ecological impacts on the North American landscape. Horses became feral and formed wild herds in various regions, including the American West, where they thrive today.

Comancheria Ruled the Southern Plains

Of all Native Americans, the Comanche made the most extensive use of horses to carve out and defend their homeland, Comancheria. This territory covered a vast area, including present-day New Mexico, west Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Colorado. The Comancheria boundaries were not fixed and varied over time, depending on the Comanche’s influence and conflicts with neighboring tribes and European settlers.

The Comanche were skilled horse riders and developed a hegemonic power on the southern Plains for over 100 years. They dominated trade, raiding settlements and controlling other Native American groups. They effectively resisted Spanish, Mexican, and American attempts to control their territory for many years. U.S. military officers called them the finest light cavalry in the world.

The Comanche built their wealth through raids and trade. Wiki says they mainly took horses to expand their power and for exchange. They also took captives from other tribes during warfare, enslaving them, selling them to Spanish and (later) Mexican settlers, or adopting them into their tribe. Thousands of captives from raids on Spanish, Mexican, and American colonists assimilated into Comanche society. At its peak, the Comanche language was the lingua franca of the Great Plains region.

But the Comanche’s reliance on horse warfare was one-sided. They carefully tended their grasslands but rarely planted other crops. Their diet was rich in meat, but they had to trade with neighboring tribes for corn, beans, and squash, thus developing a dependency.

The expansion of white settlements and military campaigns against the Comanche, such as the Texas Rangers and the U.S. Army’s Red River War, gradually led to Comancheria’s decline.

The Red River War, however, was not limited to the Comanche. It was a more comprehensive military campaign fought between the U.S. Army and various Native American tribes in the southern plains region of the United States. This was from 1874 to 1875. It occurred primarily in the Texas Panhandle, Oklahoma Panhandle, and southwestern Kansas. The aim was U.S. hegemony over all peoples in its interior.

The conflict arose due to white settlers’ encroachment onto traditional Native hunting grounds. This also sharpened tensions between Native American peoples, notably the Comanche, Kiowa, Southern Cheyenne, and Arapaho tribes. The tribes previously relied on vast buffalo herds roaming the plains. However, hunters and railroad travelers’ mass buffalo slaughter threatened their way of life and culture.

In response to increasing raids and conflicts between settlers and Native Americans, the U.S. government launched a military campaign to secure settler land takeovers and subdue and relocate the tribes to reservations. Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie led the expeditions and engagements.

The Red River War witnessed several significant battles, including the Battle of Palo Duro Canyon in September 1874. This battle marked a turning point in the campaign. Mackenzie’s troops, aided by Tonkawa and Caddo scouts, attacked and defeated a large encampment of Native Americans, capturing their supplies and horses. Following this defeat, many Native American tribes surrendered or fled to neighboring reservations.

The Red River War ended in mid-1875 when the remaining Comanche, Kiowa, Southern Cheyenne, and Arapaho tribes were forced onto reservations in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). The conflict resulted in the confinement of these tribes to reservations and the further loss of their traditional lands and way of life.

The Red River War was part of a larger pattern of conflicts between Native American tribes. This pattern included the U.S. government’s westward expansion and the quest for hegemony over its ‘interior.’ By the late 19th century, the post-Civil War military used bison slaughter to near extinction. Disease was also a factor. Outbreaks of smallpox (1817, 1848) and cholera (1849) took a significant toll on the Comanche, whose population dropped from an estimated 20,000 in the late 18th century to just a few thousand by the 1870s. With this ‘external’ help, the military significantly diminished Comancheria and confined the Comanche to reservations.

Quanah Parker was the prominent Comanche leader during these difficulties. He was born around 1845 near the Wichita Mountains in Oklahoma. Quanah Parker’s mother was Cynthia Ann Parker, a white woman captured by the Comanches as a child and adopted into their tribe.

Quanah rose as a warrior and leader and became one of the last Comanche chiefs to resist white settlements and encroachment on Native lands. However, as the U.S. government intensified its efforts to subdue the tribes and enforce reservations, Quanah realized the futility of continued resistance. He advocated for peace and cooperation.

In 1875, Quanah and his followers surrendered to U.S. authorities and settled on a reservation in southwestern Oklahoma. He became prominent in the Comanches’ transition from nomadic to reservation life. He was eventually appointed as the ongoing chief of the Comanche tribe and worked tirelessly to protect his people’s rights and well-being.

Quanah also became involved in politics and lobbied for better treatment and resources. He advocated for educational opportunities and land rights. He was known for his diplomacy and ability to bridge the gap between Native American and white cultures.

He remained a respected leader and spokesperson until he died in 1911. Quanah Parker’s legacy endures as an essential figure in the history of Native American resistance, adaptation, and advocacy. He is remembered for his leadership, cultural preservation efforts, and role in shaping the Comanche people’s future.

Today, the Comanche Nation, based in Oklahoma, preserves its culture and history. Many descendants of the Comanche people still live in the region once known as Comancheria.