Today there are about 1.5 million Japanese Americans in the United States, with the largest numbers living in California and Hawaii.

Japanese migration began in the mid-19th century following Japan’s 1868 Meiji Restoration. Japan then underwent significant modernization and Westernization. As part of this process, the Japanese government encouraged emigration as a means to learn from Western societies and acquire updated knowledge and skills.

The first wave of immigrants to the U.S. consisted mainly of young men seeking employment opportunities and economic advancement. Many came from farming backgrounds and were recruited to work as contract laborers on plantations in Hawaii. They were also recruited as agricultural workers on the West Coast of the United States. Their labor was in high demand, particularly in mining, railroad construction, and agriculture.

Japanese population growth was gradual at first, but quickened at the turn of the century. The 1907 ‘Gentlemen’s Agreement’ between the U.S. and Japan slowed down Japanese labor immigration. Still, it allowed family reunification and exempted specific categories of immigrants, such as students, teachers, and professionals.

In the early 20th century, immigrants and their descendants established vibrant communities, particularly in California. They engaged in various industries and formed agricultural cooperatives. They faced significant discrimination and xenophobia, which led to discriminatory laws and policies. A case in point was the ‘Alien Land Laws’ that restricted their ability to own land.

Despite these challenges, Japanese immigrants and their descendants made significant contributions to American society. They were called the ‘Issei,’ and the younger generation the ‘Nisei.’ Their efforts included agriculture, fishing, entrepreneurship, and cultural advancement.

The Issei were particularly noted for their gardens, not only for their quality but also for their beauty. While each garden is unique, certain elements are typically included. For example, most Japanese gardens have a koi pond representing the universe. Additionally, stone lanterns and water basins are also standard features. Of course, no Japanese garden would be complete without beautiful plants and trees. Bonsai trees are often used in these gardens, symbolizing the balance between nature and man.

The Immigration Act of 1924, however, banned all but a token few Japanese people. Earlier laws limited naturalization to ‘free white persons,’ which excluded Japanese in the U.S. from the right to vote and other restrictions. By the 1930s, Japanese immigration had dried up.

The Japanese Empire’s attack on Pearl Harbor marked a dramatic change. Japanese Americans were interned soon followed the onset of World War II, which profoundly impacted their communities.

The Interment Camps

What was the Japanese internment program during WW2? The government implemented a policy involving the forced relocation and imprisonment of approximately 120,000 Japanese Americans living on the West Coast.

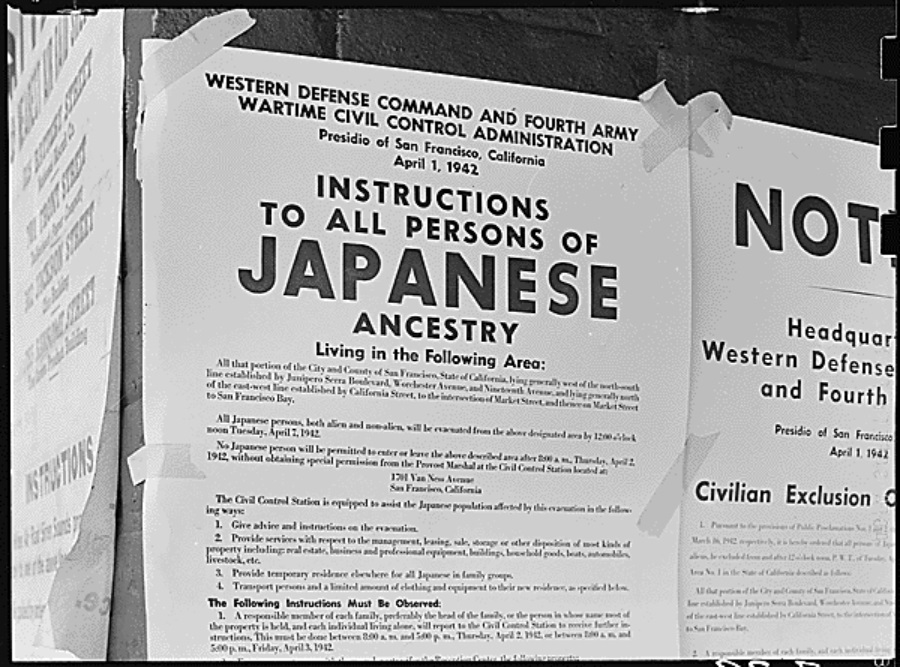

Following the Pearl Harbor attack, there was widespread fear and suspicion among the American public and government officials regarding Japanese Americans’ loyalty. The U.S. government, notably President Franklin D. Roosevelt, issued Executive Order 9066 in February 1942. This order authorized the establishment of military zones and removed individuals deemed a potential threat to national security.

Under this order, Japanese Americans, mostly American citizens, were forcibly relocated from their homes and placed in internment camps, primarily in remote and desolate areas. These camps were hastily constructed and lacked adequate facilities and living conditions. Families were often separated, and people were forced to live in cramped and overcrowded barracks.

Here are some of the significant internment camps where Japanese Americans were relocated:

Manzanar War Relocation Center (California): In Owens Valley, California, Manzanar was one of the ten main internment camps. It housed approximately 10,000 Japanese Americans and operated from 1942 to 1945.

A December 1942 incident at the Manzanar camp resulted in the institution of martial law at the camp. It culminated with soldiers firing into a crowd of inmates, killing two and injuring many. The incident was triggered by the beating of Japanese American Citizens League leader Fred Tayama upon his return from a meeting in Salt Lake City and the arrest and detention of Harry Ueno for the beating. Coming one year after the attack on Pearl Harbor, sensationalist coverage of the event inflamed anti-Japanese sentiment outside the camps. The episode exposed deep divisions within the inmate population and with the camp administration. According to Eastwind, “At Manzanar, the condescending manner, misstatements, and suspected profiteering of camp administrators added a second line of fuel to feelings of animosity and resentment. An attack on the leader of one faction by members of another, and the jailing of a suspected attacker, flamed into a protest against everyone, everything, all at once.”

Tule Lake War Relocation Center (California): Situated in Modoc County, California, Tule Lake was initially designated as a segregation center for those considered “disloyal” to the U.S. government. It became the largest and most controversial camp, housing over 18,000 Japanese Americans.

Heart Mountain Relocation Center (Wyoming): Located near Cody, Wyoming, Heart Mountain housed around 10,000 Japanese Americans. It operated from 1942 to 1945 and was one of the largest internment camps.

Poston War Relocation Center (Arizona): Situated near Parker, Arizona, the Poston camp was divided into three separate sections (Poston I, II, and III) and held approximately 17,000 Japanese Americans.

MINIDOKA War Relocation Center (Idaho): Located in south-central Idaho, MINIDOKA housed over 9,800 Japanese Americans. It was one of the ten main camps and operated from 1942 to 1945.

Gila River War Relocation Center (Arizona): The Gila River camp held about 13,300 Japanese Americans in Pinal County, Arizona. It consisted of the Canal and Butte camps and operated from 1942 to 1945.

Topaz War Relocation Center (Utah): In the Sevier Desert of central Utah, Topaz held around 8,130 Japanese Americans. It operated from 1942 to 1945 and was one of the ten main internment camps. Standing on the site today, one can feel the mixture of awe, anger, anxiety and hopelessness that must have washed over the internees who did not know when they would be released.

These are just a few examples. There were ten main camps spread across different states, along with several smaller camps, isolation centers, and assembly centers. These camps were where Japanese Americans were detained.

Japanese Americans were interned until 1945, when World War II ended. During this time, campers endured harsh living conditions and lost their personal freedoms. Many Japanese Americans suffered significant economic losses as they were forced to abandon their homes, businesses, and possessions. In fact, many of their ‘neighbors’ thought little of their potential disloyalty. They simply wanted to seize homes, businesses, and gardens for opportunist reasons of their own.

It is important to note that the internment program has been widely criticized as a grave violation of civil liberties and constitutional rights. In the years following the war, efforts were made to address the injustice. In 1988, the United States government formally apologized for the internment and reparated Japanese American internees. The Civil Liberties Act of 1988 acknowledged that the internment was based on “race prejudice, war hysteria, and political leadership failure.”

It’s important to note that while the internment program affected many Japanese Americans living on the West Coast, not all individuals of Japanese descent were interned. Some Japanese Americans could relocate to other parts of the country or were exempted from internment due to age, health, or work in essential industries.

Was it ever proven that Japanese Americans aided Japan in the war? No, it was never proven that the Nisei aided Japan in the war as a group. The mass incarceration was based on racial prejudice, wartime hysteria, and the mere perception that they posed a potential threat to national security.

After an extensive investigation during the war, the government found no evidence of widespread disloyalty or espionage among Japanese Americans. The Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC), established in 1980, also conducted a thorough review and concluded that there was no military necessity for the internment. It affirmed that mass incarceration was primarily the result of racial prejudice, wartime hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.

In politics today, Japanese Americans tilt to the left. According to Wiki: “In the 2012 presidential election, a majority of Japanese Americans (70%) voted for Barack Obama. In the 2016 presidential election, majority of Japanese Americans (74%) voted for Hillary Clinton. In pre-election surveys for the 2020 presidential election, 61% to 72% of Japanese Americans planned to vote for Joe Biden.”

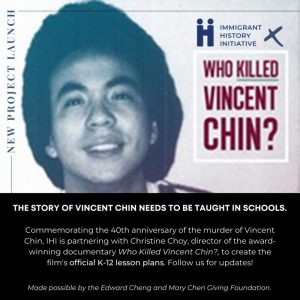

The Vincent Chin case fired up Japanese American participation in the Rainbow. During an economic recession in the early 1980s, the auto industry’s decline provoked resentment toward imported Japanese cars in Detroit, which was the center of the automotive industry in the United States. ‘Japan bashing’ became popular with politicians, such as U.S. representative from Michigan John Dingell, who blamed ‘little yellow men’ for domestic automakers’ misfortune. Nationwide, Anti-Asian racism often accompanied campaigns urging consumers to Buy American.’

This was the context for the 1982 beating-to-death of Vincent Chin, a Chinese American who his killers assumed was of Japanese descent. His killers were charged with second-degree murder, but pled down to manslaughter.

Mike Murase took part on the campaign for Justice for Vincent Chin. In 1988, he served as the California Campaign Director for Rev. Jackson’s presidential campaign and was the chief whip for the California delegation at the Democratic National Convention in Atlanta. He also did international support work to dismantle apartheid in South Africa as the coordinator of Los Angeles Free South Africa Movement and served as Congresswoman Maxine Waters’ district coordinator for 14 years.

In the late 60s, while a student at UCLA, Mike became involved in the struggle to establish ethnic studies and was a co-founder of the Asian American Studies Center. He also co-founded GIDRA, a publication that came to be known as the “voice of the Asian American movement.” More recently, he has been active in the Little Tokyo community working with a social service agency and Nikkei Progressives, a grassroots organization building solidarity among various movements of POCs.