In our ‘Side Story’ on Lord Dunmore and the western front during the War of Independence, we mentioned a battle at Point Pleasant, near Wheeling W VA, that led to the death of Cornstalk, a much-loved Shawnee leader, who was also a veteran of Pontiac’s Revolt.

Another Shawnee casualty at Point Pleasant was Pukeshinwa, also a war chief, who founded an Indian settlement in Ohio named Chillicothe. Pukeshinwa and his wife, Methotaske, had at least eight children, seven sons and a daughter. The eldest son and the firstborn was Cheeseekau, who continued his father’s insurgent battles by siding with the British against the Americans in the Ohio County. Cheeseekau was also a comrade of another prominent Shawnee fighter, Blue Jacket.

But Cheeseekau today is mostly remembered as the elder brother and mentor of Tecumseh and Tecumseh’s younger brother, Tenskwatawa, also known as ‘The Prophet.’

Tecumseh was a Shawnee leader who emerged in the battles and reprisals against the renewed American occupation of the Ohio Country after 1780. The Shawnee were particularly incensed by the atrocities of General George Rogers Clark, head of the Kentucky militia, who, over several years, made a practice of burning Shawnee villages, crops, and the Shawnee themselves. In the summer of 1783, after the ‘Treaty of Paris’ required the British to leave the Ohio Country, the Native Peoples organized an inter-tribal conference near Sandusky, Ohio.

Tecumseh attended it as a young warrior of 15 years. The gathering was headed by Thayendanegea, aka Joseph Brant, a Mohawk chieftain born in the Ohio Country, who had sided with the British against the Americans in New York.

Brant’s gathering was called the ‘Western Confederacy,’ or the ‘United Indian Nations,’ meaning a multi-tribal alliance to stop American expansion and staking the entire Northwest Territory as an independent Native homeland. Brant wanted the Confederacy to use contradictions between the British in Canada and the US. However, he had no particular love from the UK, believing they had sold out Indian rights at the Treaty of Paris. (Brant also had his downside, capturing, buying, and selling African slaves to work his own lands).

The U.S. waged a ten-year campaign against the Confederacy, known as the Northwest Indian War (1785-1795). It ended with a U.S. victory at the Battle of Fallen Timbers near Toledo, 1794. A young Tecumseh and his older brother, Sauwauseekau, fought here, and Sauwauseekau was killed. On the Native Alliance side, it was led by Blue Jacket and Little Turtle, although Little Turtle had warned against the engagement.

The key point here is that many of Tecumseh’s views were not original but had a long tradition. He would go on to take them to new heights and add fresh ideas of his own. But let’s not get ahead of our story. At this point, with the Ohio Country tribes suffering from defeats, Tecumseh’s younger brother, Tenskwatawa, was better known for his prophecies and spiritual teachings. Tecumseh, however, had solid intellectual skills of his own. He was multilingual, not only in Native languages but in English as well. Moreover, he could speak English with barely any accent and, at times, would disguise himself and travel about settler towns and camps, passing as a European-American, engaging in tavern discussions and other public spaces to learn as much as he could about his adversaries.

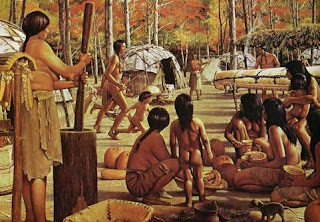

By 1808, Tenskwatawa’s teachings attracted a large following, so he and Tecumseh set out to found a secure base area, called ‘Prophetstown’ in English, near what is now Lafayette, Indiana. The settlement attracted warriors and their families from dozens of tribes. It grew into a rural city-state with more than 3000 inhabitants, one of the largest in the Ohio Country. Attracted by the charismatic teachings of the Prophet, the settlement served as a political and military school. The two brothers aimed to use it to forge something more than a loose alliance, but a new and tighter ‘Red Nation’ identity that saw all of the Northwest Territory as their autonomous and self-governing homeland.

However, the new U.S. government had other plans for the Northwest Territory and had already planned subdivisions for settlers to form new states. By 1800, William Henry Harrison had been assigned as the governor of the Indiana territory, with its capital at Vincennes. Harrison had also fought at the Battle of Fallen Timbers opposite the young Tecumseh as a young man. Later, he turned to negotiating skills, discarding, writing, and rewriting dozens of new agreements for Indian land cessions. Where he ran into opposition, he would work to subdivide a tribe or group of tribes, offering high payments to some and then using the division to isolate others. His troops were always ready at hand should he need more substantial incentives. By 1809, he had acquired nearly 3 million acres in the Treaty of Fort Wayne.

Tecumseh and his allies strongly denounced the Treaty of Fort Wayne, declaring it null and void and violating earlier treaties. In August of 1810, Tecumseh agreed to a meeting with Harrison in Vincennes, arriving with 400 warriors in war paint. Refusing to make land cessions, he also told Harrison he would kill or dispose of any Native leaders who did otherwise. The exchange grew heated, and another chief present moved to close the discussion before it turned violent. (Harrison later informed his superiors that he was impressed with Tecumseh, and should his confederacy gain strength, it would be a powerful adversary to the U.S.).

Tecumseh again traveled widely for the next year, promoting his confederacy and winning recruits to Prophetstown. He also went to Canada to meet with his old adversaries, the British, and explore an alliance with them to move the Americans out of the Northwest Territory and away from any designs they might have on parts of Canada. In July 1811, he returned to Prophetstown and agreed to meet again with Harrison at Vincennes, not too far to the south. Neither changed their views, but Tecumseh informed Harrison that his confederacy was expanding while he was not seeking war.

In Gramsci’s terms, Tecumseh was waging a ‘war of position,’ gathering strength, allies, and resources. He made one mistake, however, by informing Harrison he was off for another long trip. Tecumseh knew his brother was impulsive and a hothead and warned him not to engage in head-on battles, or ‘wars of movement,’ with Harrison until he returned and they could assess their strength. Harrison saw an advantage and sent a few troops to provoke Tenskwatawa. It worked. Tenskwatawa engaged in the battle but quickly faced Harrison’s far larger main-force attack. It’s known in U.S. history as the ‘Battle of Tippecanoe,’ after a nearby river. Harrison’s troops overwhelmed Prophetstown, routed the residents, and burned it to the ground.

On Tecumseh’s return, he chastised his brother, but the two remained a team, with Tecumseh as the politician and military leader and Tenskwatawa as the spiritual force. They rebuilt Prophetstown, which soon housed 800 warriors, with another 3500 nearby. Tecumseh had sensed that the British were on the verge of war with the Americans, and while they were strong on the Atlantic coast, they were weak in the west.

In 1812, Tecumseh decided it was time to fight. After winning several minor skirmishes with the Americans, he went to Fort Malden in Ontario to meet with British General Isaac Brock, in charge of ‘Upper Canada,’ as Ontario was called at the time. The two immediately bonded with each other with mutual respect and worked on plans to take Fort Detroit back from the Americans. The American General at Detroit, William Hull, had been taking his troops into Canada. Tecumseh arrived in Detroit with about 500 warriors, but he moved them above so cleverly that the Americans thought he had many more. Hull surrendered without much of a fight, to the surprise of all. Wikipedia reports that British General Brock had this to say of Tecumseh:

“He who attracted most of my attention was a Shawnee chief, Tecumseh, brother to the Prophet, who has carried on active warfare against the United States for the last two years, contrary to our remonstrances. A more sagacious or a more gallant warrior does not I believe exist. He was the admiration of everyone who conversed with him.”

Tecumseh continued engaging the Americans in battle over the next year. He won some and lost some. In May 1813, his forces came out on top at Fort Miami and captured many of the Kentucky militia. The Native warriors were torturing and scalping a group of prisoners, well within their traditions. But Tecumseh inserted himself into the grim event and stopped it. (Nor was this the only time) Tecumseh held that such acts demeaned not only the victims but also those doing the torturing. He wanted no part of it, and likewise for those under his command. News of these acts of compassion spread during and long after Tecumseh’s time and contributed to his stature. Decades later, in the Civil War, a top U.S. General was William Tecumseh Sherman. His middle name was viewed honorably, even though those who resided in Georgia and experienced his ‘March to the Sea’ might think otherwise of him.

When the British struct a truce with the Americans in 1813, Tecumseh saw the writing on the wall. In September 1813, he moved to Canada to aid his allies and fight the Americans. He was vastly outnumbered, and many of his warriors departed. A core of 500 remained and fought it out at the Battle of the Thames. He was killed in fierce combat, and American soldiers proceeded to scalp, skin, and dismember his body for ‘war trophies.’ Exactly where his remains were buried is not known.

The War of 1812 thus was a double victory for the Americans. After being humiliated by the burning of Washington, DC, they had now pushed the British away from the Atlantic shore. But they also succeeded in defeating the prospect of the Northwest Territory as a homeland for a ‘Red Nation.’ After their collapse in the Ohio Country, the Native people faced extermination by guns or disease or the need to move further west. The war ended in 1814 at the Treaty of Ghent, with a young John Quincy Adams among those who put it together. But the news of the peace took weeks to cross the Atlantic, giving Andrew Jackson the prospect of one last routing of British forces in the Battle of New Orleans. The battle itself was not decisive, but Jackson’s victory was. In a short time, it would open a new phase in American politics.